|

| Combat and Magic |

|

| Spoiler: Mummies |

Role-playing in Hungary does not have a particularly

long history. It is telling that people who had started in the early 1990s are

considered veterans of gaming, a generation which would barely count as

neophytes in the US or the UK. More than that, we know little of that early

gaming period. From the first groups in the mid-1980s to its first boom of

popularity in 1990-1992, precious little material evidence has remained. By all

accounts, people had fun playing (mostly) AD&D, and photocopied

translations were circulated among fans (the best known version being The

Ruby Codex), but the publication of homebrew materials was minimal, or at

least extremely limited. It was a different time: photocopiers were hard to

access, and home (or even workplace) printers were expensive equipment mainly

found in research institutes and universities. Therefore, we cannot really

speak of an age of fanzines, nor extensive home publishing. I know of (and own)

one homemade module which was available at the time: The Great Pyramid,

a mid-level dungeon whose themes and ideas should be hardly surprising.

Without external support, game groups had to make do

with what they had: a few fantasy novels (Tolkien, a dash of Conan, and some disreputable but fun pulp literature), the occasional photocopied game supplement they could get from other

groups, an increasing number of computer games, Fighting Fantasy, and their

imagination. The results were varied, from the deadly dull to the quite

imaginative (or at least somewhat original). One of these results is Combat

and Magic [Harc és Varázslat], the first Hungarian RPG, whose brief

appearance and fast downfall went mostly unnoticed at the time. But not by all:

this was the first “real” RPG I ever played (after a systemless dungeoneering

game at the Scouts I then believed to be an innovative sort of puzzle), and I

still have good memories of the experience, even though in my first adventure,

my nameless Fighter went down into some mines and got summarily killed by orcs

in one of the first encounters. I barely knew what hit me, but I was hooked!

Thus, this post: part reminiscence, part a look at a

game that’s both utterly predictable and compellingly oddball, a product of a

naïve fascination with fantasy literature and an exciting new game form.

***

Combat and Magic was published

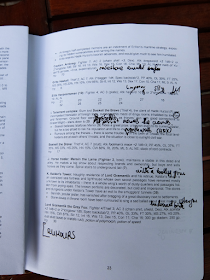

in 1991 by the completely unknown company “SPORTORG Ltd.” Its authors, Tamás

Galgóczi and Péter László were AD&D players (a decade later, I would buy

Galgóczi’s lovingly bound and much used photocopies of the 1st

edition AD&D rulebooks – these ancient bootlegs are as treasured parts of

my collection as my OD&D set), and they had planned to spread their hobby

through an introductory game, to be followed by more “advanced” supplements down

the line. Combat and Magic comes in the form of two full-sized 56-page

booklets, one for the players and one for the Gamemaster (called, according to

local custom, the “Storyteller”). The second booklet also includes a folded map

of the three-level intro dungeon (on which more later), and the whole package was

originally sold with something called a “lucky die”, a ten-sider! (Considering

the difficulties involving in obtaining a d10, people would apparently buy the

game just for the die alone.)

Combat and Magic proudly wears

its influence on its sleeve. The cover on the players’ booklet is graced by a

notoriously bad rendition of Frazetta’s Conan the Destroyer fighting some lizard-things, while the Storyteller’s booklet depicts a

scene right out of Tolkien, an adventurer menaced by something that looks like

a ringwraith. The Conan-meets-LotR theme continues through the entire game in a

strange manifestation of schizophrenia – sometimes the game has its semi-naked

amazons, war galleys and buff fellows in leather gear holding various murder

implements, and sometimes we are in Moria or Rivendell (and not a homage

either: it is clearly Frodo and Co. investigating the tomb of Balin, facing the

Balrog, or finding the mountain door).

|

| An American Fantasy Game Similar to Combat and Magic |

As the introduction proclaims, “You have surely

read J. R. R. Tolkien’s exciting book, The Lord of the Rings. This game leads

you to a similar world, and you can live there, adventuring among the creatures

of fantasy. You can meet goblins, elves, dwarves, dragons, and you only need a

little imagination... If you like our offer, forward to adventure! You are

awaited by the forbidding lands of the unknown world, its cities and peoples!

Your imagination will wander the land of fantasy, the world of DRAGONFLAME...”

In a charmingly earnest way, it goes further – the back cover of both rulebooks

reproduces the cover of the Mentzer Set, the caption reading “The cover of

one of the American fantasy games similar to Combat and Magic”. Similar

indeed! Interestingly, just like Original D&D was billed as “Rules for

Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns”, Combat and Magic is called a

“Personality Game” (and on at least one occasion, a “Cooperative Personality

Game”), and not an RPG – no common local term for RPGs having been accepted

yet.

***

|

| Vorg saves an old Priest |

As introductory games go, Combat and Magic is

remarkably newbie-friendly. The future player is guided on his journey by “Vorg

the Wolf”, an in-game character. Vorg, a 7th level Fighter, is

somewhere between Conan and a wise Indian from a western (showing that the new

concept of the barbarian had not yet taken solid shape in the local

imagination, and the gaps were filled in by prior references). We first meet

Vorg in a short story where he seeks out, confronts and kills Surat, the dark mage

who had recently decimated a village, and now lives in a dungeon under a ruined

castle built by the dwarves (“You have come to the right place if you seek

Surat! He is I!” and “You wanted to kill me, warrior? You shall die

instead!”). Vorg helps the player at all stages of character creation,

introducing game concepts from an in-character stance that is at once weird,

wrong, and completely charming. (“I, Vorg, the wolf, the highest level fighter

among the long-haired ones, say to you that the most important attribute in the

world is Strength.” Or: “You have surely read my adventure. The

personality sheet for Surat the evil Mage would look like this: Intellect 88%.

Number of languages 4, modifier +30 days. He knew four foreign languages before

I killed him, which he had learned over half a year and +30 days. By my sword,

I say it was a great accomplishment that I had destroyed him!”)

The game, not surprising considering its AD&D

roots, uses seven attributes, but measures them on a percentile scale

(Intellect, Strength, Agility, Speed, Endurance, Manual Dexterity and Physical

Looks). Yes, they are rolled with entirely random 1d100 rolls, in order, no

takebacks. Or as Vorg tells us: “Let us begin, and may the gods guide your

hand!” These attributes provide modifiers for a whole lot of secondary

values from combat ratings to poison resistance and the ability to read and

write (Vorg, with a Manual Dexterity of 8%, is completely illiterate, and his

14% Physical Looks is fairly dire – but he has an impressive 92% Strength). Some

people say chicks dig scars, but this is clearly incorrect on the world of

DRAGONFLAME: when you receive face wounds in combat, your rating drops pretty

substantially. On the other hand, chicks receive a 1.2 multiplier to their

Physical Looks because “If your personality is a woman (…) you take better

care of yourself and your beauty.” On the other hand, many other modifiers

are fairly moderate, and much of the attribute range does nothing whatsoever or

very little: there is, for example, no difference whatsoever between an

Endurance of 26 and 70.

|

| Haven't we seen this before? |

Combat and Magic has a fairly

weird Vitality system: every character starts with 100 Vitality, plus

race-based dice (Elves have 1d10 more Vitality, Humans, Goblins and Orcs have

2d10 more, and Dwarves have 3d10 more). At 0 Vitality, you are dead. However,

the system also has something called Damage Absorption Percentage (DA),

which starts at 20% of your character’s full rating, and goes up 2% every

level, up to 38% (Fighters also gain a one percent bonus per level, but none of

the other classes do). Should you receive more damage than this percentage, you

fall into a comatose state, where you bleed out at a rate of 1 Vitality per

wound per round – only healing can bring recovery. In practice, your average

longsword does 1d10 damage, a staff does 1d5, and a cavalry lance – the

mightiest weapon – does 1d10+10, so a few successful hits can dispatch even a

relatively hardy character. As an obvious AD&D legacy, saving throws

(or their equivalent, “Chance Rolls”) also exist as three flat percentile

ratings to escape the effects of poison, magic, and dragon breath, respectively

(although dragon breath, an oddly specific choice, still causes half damage).

The real rating which matters is your DA: it is not entirely clear why the

ridiculously high total Vitality is used at all.

|

| This looks oddly familiar |

From classes (or, rather, “castes”, a really

bad word choice which would then gain traction and crop up in almost every subsequent

Hungarian RPG), the system offers four: Fighters, Trackers, Priests and Mages.

These are somewhat less restrictive classes than D&D traditions would

dictate: there is little difference between different classes when it comes to

Attack and Defence %, Vitality or Chance Rolls; rather, each class gives a

basically competent adventurer a set of bonuses and limitations. Accordingly,

- Fighters learn to use multiple weapon types, and have slightly better combat values. Noble fighters (player’s choice to try for a 75+ percentile roll) get training with more kinds of weapons, but suffer a small Endurance penalty. Nobles also have to abide by a code of conduct: they may only attack a woman in self-defence, they must always attack from the front, and they may not use poison (“except evil nobles, because they are capable of it”). Even evil nobles, as we learn, “Follow etiquette, and only rarely have their captives tortured – and never by their own hands.” Their commoner counterparts start with a small penalty to either mounted or footman’s combat, which they “grow out of” by level 5.

- Trackers are skilled hunters, who either work alone, or as guides to travelling companies. They can call an “animal companion”, with one attempt possible per level (if it is a failure, the beast attacks). A tracker must avenge and mourn two years for a companion if it is ever slain before calling another. They also have versatile wilderness skills: tracking, speaking with animals, hiding, and recognising traps.

- Priests are spellcasters, who, unlike fighting classes, can only gain levels by returning to their churches, where they are also required to donate all their unneeded money. Priests are either Good or Evil, but never Neutral (this will become important a bit later). They are not limited by weapon type, but only know to use a few of them (up to 4, while a Fighter would start from 3-4 and proceed from there). Priests can contact the gods directly for advice and help. They also have a bunch of different abilities based on the specific god they worship, who are quite varied. The followers of Perlin, goddess of dreams and fairy tales (Neutral, Priests can be either Good or Evil) can perform divinations, but they must regularly interpret a dream as a form of sacrifice; meanwhile, the Priests of Dorl, god of earth (Neutral, Priests must be Good) have a special spell to hurl pebbles, can sense buried items under their feet, but they must bring home a clod of earth from every land they have visited, and can only use bludgeoning and cutting weapons.

- Mages aren’t D&D’s physical wretches (having lower, but still passable combat abilities and Vitality), although they are limited to daggers and staves, and must not wear armour. They must return to their master to gain levels. Mages belong to one of two schools: Moonlight Mages are Good, and practice white magic; while Grey Mages are Evil, dealing in black magic (these orders also give their members assistance if they show the correct hand signs). Mages sense other spellcasters in a 10 metre circle.

After you determine your class, you must also roll

for social status. This is another flat 1d100 roll,: you may start with 40

copper pieces as a “free homeless” (1-14), 1 gold piece as a servant (15-29),

75 gp as one of the “famed” (75-84), or 1000 gp as royalty (00). For reference,

10 gp is the price of a longsword, while for 1000 gp, you get a suit of plate

mail.

Like true-blue old-school games, there are no

skills in Combat and Magic. However, your character may have a

profession, unless you are a noble fighter, because work is beneath

nobles. Your choice of profession depends on your social status, your ability

scores (with some racial bonuses and limitations), and your class. Here, Combat

and Magic again delves into the oddly specific, letting you play a more

conventional healer (restore up to 10 Vitality per week), sailor (you can

navigate ships) and thief (you get the thief skill), or professions like

a gravedigger (you recognise religious symbols and tolerate the stench of the

grave), executioner (you can easily kill restrained victims) or miner (you

don’t get lost underground). Your profession is, once again, rated at an

utterly random percentile value, which never, ever improves. You might

be the best weaponsmith out there with a 100%, or you can be a random fool who

drops the hammer on his feet with a 3%.

|

| Ironically, neither six- nor four-sided dice are featured in Combat and Magic |

Combat in the game is a fairly straightforward but

ultimately quite fiddly you-swing-I-swing affair based on an Attack % and a

Defence %. Both of these are modified by a whole range of tiny little things which

are individually minor, but can add up if taken together

- In each round, characters must decide to either attack their opponent or forego it and defend themselves.

- Initiative is a simple d10 roll for your whole group.

- Your Attack % is used to figure if you score a connecting hit.

- Armour (if any) can stop a blow outright, based on a matrix cross-referencing five armour types (leather, studded, chain, scale and plate) and three weapon types (piercing, slashing and bludgeoning) that’s reminiscent of AD&D’s infamous weapon-vs-AC chart. For instance, chain is 25% vs. piercing, 50% vs. slashing, and 35% vs. bludgeoning.

- If a hit is scored, but the subject has chosen to defend himself instead of attacking, he can still roll a successful Defence % to avoid getting hit. Many weapons grant a bonus to Defence %, from 10 (daggers and hammers) to 15-20% (most swords and maces) to 30% (polearms), and you also get some from shields (10% or 20%), but you must choose whether you’d like to defend with your weapon or your shield.

- If neither form of defence succeeds, you get to roll damage, which, as previously noted, can be pretty dire.

This system comes with a fair whiff factor,

although Defence % tends to be fairly low, and if you know enough weapons, you

can use one which gives your opponent a lower Armour roll (it pays to stock up

on different weapon types).

|

| No, really |

Spellcasting in Combat

and Magic uses a spell point system: both Priests and Mages have 10 spell

points per level, recovered through meditation (Clerics) or 1d10 hours of sleep

(Mages). It is possible to cast spells over one’s point limit, at a risk to the

character’s sanity (the chance of escaping unharmed is 70% the first time, 40%

the second, and a mere 10% the third). The spell list goes up five levels, and

beyond the Wizard/Priest split, each spell is also associated with an

alignment. Characters can use spells of their own alignment, and neutral ones

(remember, spellcasters can’t be neutral). The spells themselves are mostly

D&D ripoffs (Hebron’s Smashing Fist, Call Monster I, Tiny Hut, Prayer...),

but there are also some compelling oddities, such as…

- Almos’ Blue Parasol: protection vs. falling rocks, hail, and rain spells

- Hair Growth: uncontrollable hair growth entangles victim

- The Quarrelsome Door: creates a talking door

- Dream Voyage: the victim sleeps for 1d10 days, dreaming of a fantastic voyage that feels like the same number of years, and ages accordingly

- The Dark Blue Berries of Pavlovich: creates 30 berries, eater sleeps one day for each, losing 2 Vitality per day

|

| The lands of Rôhen |

Although the Storyteller’s Booklet is

dedicated specifically to running the game, and players are admonished to avoid

reading it, it starts with a brief world guide that would probably be a better

fit for the main rules. The world of DRAGONFLAME (no longer capitalised here)

is a naïve fantasy mishmash, but it has its own creation myth, and a huge,

active pantheon of gods with quite silly names (Kayar, Zomur, Serlafor,

Zorikon, Xirfon etc.). The planet of Rôhen (note the Tolkienesque diacritic)

has three continents, but the game is focused on one called, appropriately

enough, Draco, and specifically its north-western corner called the Four

Kingdoms. To keep with the tone from the LotR appendices (the definitive

model for fantasy world-building in early 1990s Hungary), Draco’s history is

punctuated by a lot of blood and thunder, like “the Second Metal War”, “the

rise of Tarrakis, Lord of Darkness” (he had the Twelve Knights of Death on his

side, but was eventually driven out of the known world), “the foundation of

Divide” by King Farseer the First, “the imprisonment of Agay Khenmare of the

Threadbare Cap and eight demon by the Moon Mages”, and “the Second Dragon War”.

|

| Three of the Four Kingdoms (the Kingdom of the Dead Land is off to the east) |

Draco’s geography is no less fancy, with a giant

inner sea (divided into the Sea of Three Moons, the Sea of Two Moons, and the

Cold Sea), and a bunch of doggerel toponyms like Faradas, Eld Virg, M’Bo,

Búrnan and the Forest of Gerildor. However, the published game is

focused on the so-called Four Kingdoms, to the north of Shadia, and east of the

vast Orc Swamp. Actually, only three of the kingdoms are nice places to visit:

the Kingdom of Black Land, the Kingdom of Lagos, and the Bonecrusher Kingdom,

whose ruling dynasty has died out, and left behind a war of succession (the most

likely successor, Ed Morrison, lives in the town of Helltop; the capital city

is named Skull Hill, but the kingdom is actually a fairly normal place with a

sheep-based economy). This is less true about the Kingdom of Dead Land, whose

southern part is a confederation of independent mercantile towns, but the north

has been taken over by bandit gangs lead by the evil wizard, Agay Khenmare of

the Threadbare Cap.

|

| Pretty sure this is Éowyn or Galadriel |

This mini-setting is quite charming in its own way;

half Tolkien, half AD&D, but with the Northwest-European cultural

references exchanged for a decidedly Hungarian perspective. This is quite

intriguing, since the Hungarian fantasy genre, and Hungarian RPG fandom in

specific has shied away from its own history and culture. It is still a

European mishmash ranging from Finland and France equivalents to something

feeling a bit like fantasy Ukraine (with NPCs named Pierre Vandel, Oleg Isakov,

Stefan Schaller, Valdemar Kanagas, Commander Tony Elton, and Arnold Denman),

but there is something almost indescribably Hungarian about the land’s large

plains, agricultural towns and, above all, the slightly rustic tone of its

place names. As strange as it sounds, this familiarity is the strangest thing

about the whole Combat and Magic experience, because nobody has ever

tried anything like this again – Hungarian fantasy has focused on discovering

the fantastic in distant lands, to the neglect of our own.

The majority of the Storyteller’s Booklet is

occupied by the obligatory monsters and treasures. Like the spells, much of

this section consists of AD&D ripoffs and a mish-mash of mythology and the

stuff you lift out of every fantasy book you have read and liked – that is, it

is derivative but actually pretty good. Some of them come from the excellent Book

of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges, such as the Bao a Ku (a monster

tied to a set of stairs, which becomes more and more real as someone goes up,

and attacks on the top), and some are just strange in the way RPG bestiaries

can be strange:

- the Dorag is a huge blue snake with two feathered wings, which lives until you cut off its head… twice;

- the Ilmex resembles a rug with a wavy edge, with three three-fingered hands on each side, and a bird’s head perched on a long, thin neck at the front – it is a subterranean predator;

- Armoured Toads are... toads in black armour, with a hop attack;

- Fuzzballs! They are big fuzzballs with... legs capable of long jumps up to three metres. And a large toothy mouth. “They are always on the move to attack any kind of mobile meat.”

- The Vilotoner is a mixture between a huge eagle and a bat. It is very intelligent, able to converse in three languages, and cast Wizard spells. It is curious, vain, egoistic and easy to offend.

|

| The Caverns of Singing Mountain, LVL I-III |

There is some decent guidance on setting up and

running a game (actually, more than many subsequent Hungarian games, which

often wouldn’t think too deep about the question), and a bunch of

Storyteller-specific rules, but the other big interesting thing about the

booklet is the example scenario, The Dragon of Singing Mountain. Nothing

less than a three-level dungeon, it is a tutorial for both the players and the

Storyteller. You have to defeat a dragon and save a kidnapped princess – but

before that, you have to get through the caverns of Singing Mountain. The caverns

– really dungeons – are mostly linear, and the action largely features combat

and basic exploration. You get to fight morlochs, dog-headed men, a wererat,

skeletons, zombies, black dwarves, and an evil wizard. There is an underground

smithy, an evil temple (the idol has gemstone eyes and a poison gas trap), a

mirror room, a plant room (with life-draining plants), a library and a well,

but disappointingly, it lacks the wahoo nature of some of the rulebooks..

What is interesting is how the adventure starts in

a way that explains everything to the Storyteller, with a

choose-your-own-adventure structure and readout text, and starts to hand over

more and more responsibilities as it goes on. The first level is full of

handholding, but halfway through the second, the room descriptions become

sparse outlines to be filled out on your own. The third level, with a deep,

dark underground lake, is only described in brief and left to your development:

here lives Tungar the Dragon in an island tower, there is an old orc Priest who

serves as the ferryman, and other mysteries are also in evidence.

***

Is Combat and Magic a good RPG? Not really. It

is simultaneously awkward and simplistic, with fairly fiddly rules to realise

simple concepts. The character generation is more complicated than in AD&D

for less mileage, and the combat system has its awkward spots. There are puzzling

ideas, like the Vitality/Damage Absorption concept. I don’t think many people had

played by the book – I am pretty sure we didn’t, because the combat I remember

was far deadlier than the baseline. I do not count the game’s high randomness

as a design mistake (although many people in the 90s would, if they had even

heard of it); it is endearing and almost feels fresh in our day. In practice,

all those flat 1d100 rolls would tend to even themselves out, and your

character would have a few areas where he would be better than the others (at

least I don’t remember my PC being overshadowed, which definitely did

happen in our attempt to play M.A.G.U.S.,the second Hungarian

RPG.

Seen through modern eyes an incredible 27 years

later (has it really been that long?), the areas where Combat and Magic feels

fresh is the enthusiastic spirit of adventure, the way it embraces the

fantastic, and the way it tries to make most of a very narrow set of

influences. It owes a lot to The Lord of the Rings and it owes just as

much to AD&D, but there are a few things there which are beyond

imitation.

Why did Combat and Magic disappear from the

public consciousness, so much so that most gamers have never even heard of it?

In a way, it came too early, at a time when there were no established

communication channels for roleplayers yet – no magazines (the first would come

out late 1992), no fanzines, only two game stores in the entire country, and often

little contact between the isolated gaming groups out there. Interestingly, the

game was by no means unknown. I know multiple people who have started

with it, usually for a few months before they would find their way to AD&D

(either the bootleg translations or the real deal). It was also a mainstay at a

few game clubs; apparently, fans in the city of Miskolc had come up with

multiple typewritten fan supplements and their own shared setting (“Sword World”).

Combat and Magic had sold well

enough to merit a follow-up, and its creators had ideas to bring it forward

with new booklets. What happened to it was much more banal: the owners of the

publisher, SPORTORG Ltd., had just disappeared with the money and let the

company go bankrupt. It was not an uncommon way to make easy money those days –

most of these cases would never be solved by a sluggish unprepared court

system. It was an ominous sign of things yet to come – and as we will see from

later parts of this series, far from the last case where legal issues would intrude

upon the hobby.

“And now, stranger, the time of farewells has come.

I have told you everything I know about the world of fantasy. I bid you

farewell, for I am called by faraway lands, furious battles, and by glory…

perhaps we will meet again somewhere. Only the gods know. Good luck!

--Vorg, the Wolf”

|

| What price glory? |