The Hollow

Tomb (2022)

Curently Smoking:

Imperial Beetroot Blend

by Harry Menear

Published by Noisms Games

Levels 2–4

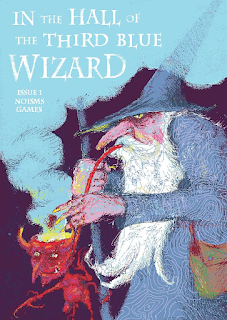

Enjoy being lost In the Hall of the Third Blue Wizard? If so, this new zine/anthology edited and published by David McGrogan might be of interest. The following reviews will focus on the adventures in the recently published first issue. As the call for papers (appropriate, as the book looks and feels like a scholarly journal) specified, submissions would be expected to be between 2000 and 10,000 words, and they tend to be on the brief side. This is both an opportunity and a hazard. Constraints can encourage efficient writing, but they may also limit the scope and complexity of an adventure. It is a fine balance to walk. Appropriately, some of these reviews will also be on the short side. It is a fine balance to walk.

* * *

A small tomb lair integrating a plotline involving a family tragedy. The real tragedy that tends to happen in adventure design is doing precisely this thing, but like classic tragedies, people just cannot be deterred from making obvious bad decisions, then suffer the predictable consequences. For all that, The Hollow Tomb does some things fairly well.

The tomb itself, a two-level affair with 19 keyed areas, is the site of a noble family’s downfall. Lady Ingmar Urquost-Blut (of a decidedly male name) was drowned by her profligate husband, Gregor Blut, who was in turn finally found out and slain by his grieving father-in-law, Lord Vodcheck Urquost. Now all three haunt the place as special undead, obsessed with their respective fates. Meanwhile, a bandit gang of “political dissidents, doomed romantics, graverobbers, or footpads and cutpurses” have occupied and plundered much of the upper level, increasingly aware there may be more to the place than what they have found so far.

Where The Hollow

Tomb thrives is in its attention to tone and incidental, vivid detail. It is

set in some vaguely Ruritanian land of scheming boyars and wheat fields; the

bandits are not just robbers but lads reading romantic poetry and cheaply

printed political literature; and the tomb’s encounters are competent at

selling it as Lord Vodcheck’s crumbling monument to his grief. Half-flooded

passages, a watery oubliette with Gregor Blut’s chained skeleton on the bottom,

and the decay of a family tomb are the high notes. There are limits to all

this. In this brief scenario, the broader setting – which sounds intriguing in

the few broad strokes it receives – does not play a functional part. The

personalities of the bandits will probably not play one either, as the

encounter with them is heavily tilted towards an armed confrontation. The

family tragedy which forms the central puzzle is reasonably well integrated

into play, but involves a major info dump in the form of a diary with Mucho

Texto (probably much better if given to players as a handout than as boxed

text).

Upper Level (tiny)

The encounters are competently done. Monster placement is quite fine. There are environmental hazards and man-made traps, decent magical puzzles, and an exploration element that is tightly integrated into the environment. A secret room can be accessed with the help of musical notation, or excavated physically. Thigh-high water conceals nasty traps. You can mess with the architecture to get into places. There are limitations posed by the module’s scope – you can only do so much in 19 keyed areas over only 5.5 pages, one of which is occupied by the maps. The writing is a mixed bag. It is at its strongest when the author just describes things naturally – this is expressive and even vivid, with a strong sense of identity. It is much weaker when it is hammered into modern fads of supposedly superior “technical writing”. The end result is neither elegant nor any more usable than the traditional model. Consider this room summary:

“Sarcophagi

(smashed open). Valuables (gathered up treasure from the coffins and

piled in a corner. 800 gp in jewelry and coins). Marble frieze (dominates

the East wall, depicts Ingmar playing the harp…” (etc.)

This description offers no advantages over simple descriptive prose, even though the text fragments, in fact, use good wording and strong imagery. This is a case of questionable “good practice” stifling actual writing talent. Sentences were developed for a reason, and this is one thing that separates modern man from the guttural shrieking and grunting of gibbering subhumans. I highly recommend trying them.

In summary, The Hollow Tomb is a flawed mini-module, but it is playable, and offers glimpses of good stuff. This is something that could be the beginning of something developed further and designed on a larger scale. For all its issues: definitely not bad. There is promise here.

No playtesters are credited in this mini-module.

Rating: *** /

*****