“The

point is the culture that drove 2E. It wasn't a

Zeb

Cook anomaly, he was just a prominent

individual

steeped in the overall boring-as-hell

“hail

m'lady” culture, overdosed on sage,

nag champa, and witchy bush.” – EOTB

“Why so mean?” , asks the man inviting the whole world into the big tent until the noise within swells to an unpleasant cacophony, rubbish accumulates, the venue gets thrashed, tentpoles are removed from their place by loud people who don’t believe tents need them, and the whole edifice collapses on the ugly spectacle. Many such cases. After the Artpunk Foe, let us now turn our attention to the sinister menace of second edition.

* * *

|

| Terrible. |

You also get cognitive blind spots where your definition shall lead you astray. For example, parts of the old-school crowd are so wedded to B/X purism and its procedure-based gameplay (“the gameplay loop”) that that they end up ignoring AD&D, and with it the actual defining tradition of the classical era; as well as neglecting OD&D, the wild primordial soup of runaway creativity that gave us the strange thought experiments that are now worth examining and reconstructing. In comparison, Moldvay/Cook is good but you will eventually run into its limitations if you don’t use AD&D’s case law to interpret it; and BECMI is a bland game that hacks away the rough edges so successfully that nothing interesting is left. BECMI is the SKUB of D&D. And then there is 2e.

In recent years, you can see a common approach to define “OSR” by viewing it as a single continuum which was broken when Wizards of the Coast overhauled the D&D system, and released the 3e books. As long as you are on the “TSR” side of the divide, you are OSR. There are persuasive arguments which support this position, at least on the surface level. There is mechanical compatibility. People can get tribal over OSE vs. B/X vs. S&W vs. LL (they are the same darn thing), but once you take a deep breath, you can convert materials on the fly among these systems with minimal effort. Even in a worst case scenario, the gaps will never be insurmountable. Game concepts are recognisable across the board. The vocabulary is common. There is personal continuity through the TSR years (although the endpoints have barely any connection at all – David Sutherland, Skip Williams and Jim Ward were the main people who were there from the beginning to the end). There is also a web of references that form the D&D “lore” (this is a magical Renfaire glitter pony of a term I am using only to express my utter disdain for it), exemplified by things like the drow, beholders, the planar system, or the hand of Vecna.

|

| The Worst Encounter Ever |

Now this probably does sound a bit extreme. “The OSR Taliban” was not a term of endearment. Some of the debates surrounding the emergence of old-school gaming were ugly, bitter, and acrimonious. But clarity is often like that. You don’t challenge common wisdom without creative conflict. You can’t play “right” without also identifying “wrong”. In the end, old-school gaming has thrived on this wedge issue. It shone light on a neglected approach to play, it established its distinctive identity, and gained bountiful creative energies in the process. These energies still drive it, although much of the momentum has naturally become exhausted over time, or become unfocused.

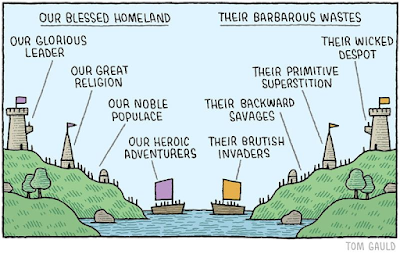

Let us now make a brief attempt to explain where the points of disagreement lie. There are a lot of details which are incidental, or which have little significance on their own, but work their way through small, subtle shifts that add up. Instead, let us try to look into the heart of the thing: two visions of (A)D&D which look very close from a distance, but are very far apart on a more careful look. These are not detailed comparisons; rather, they try to capture the respective essence of the two, and why these are not interchangeable.

* * *

For all their continuity and rough compatibility, AD&D and AD&D 2nd edition are far enough from each other to be different games. They rest on different literary traditions, their rules serve different purposes, they place emphasis on different sorts of adventures, and they play fairly differently. You can easily see this by their online communities, which generally do not mix or even communicate much.

1st edition AD&D is a single man's vision about a broad, campaign-level implementation of D&D. Its stylistic quirks and idiosyncrasies make it a personal work, even if he did, in fact, get help from a tight, handpicked design team who had helped him refine his ideas. Gary Gygax had peculiar tastes in fantasy, even in his generation: he had little interest in Tolkien and other sorts of epic fantasy, and instead liked violent sword & sorcery pulps and books on historical warfare. His main sources of inspiration were Jack Vance, Robert E. Howard, and Fritz Leiber, although he had even more eclectic tastes, and an uncanny ability to adapt ideas into the game, from 50s SF blob monsters and flying saucers to Japanese plastic toys.

|

| Wenches n' Renfaire Dorks |

The mechanics are often baroque in their totality, but they can be scaled well (this feature is one that is shared by 2nd edition). The game comes with a badly edited and rambling but supremely useful Dungeon Masters Guide which offers solid and wise advice on constructing adventures, and setting up a complex, interconnected campaign that's more than the sum of its parts. In its first years, it was also served by a very solid collection of adventures, which were very thoroughly playtested, and still serve as the most consistently good collection of scenarios for any RPG (early Warhammer Fantasy and CoC come close in their own niches). These modules are slightly different from the campaign-oriented vision of the core books: they are good, but they are often convention scenarios with standalone premises and higher deadliness for competitive scoring.

|

| A Paladin in Art Hell |

The ideal of the 1st edition campaign is not as tightly structured as some interpretations of B/X, but it does have an implied arc. From frontier localities threatened by dark forces, characters grow in stature to embark on lengthier and more complex adventures, until they can establish domains, embark on extraplanar journeys, or descend into the depths of the earth. There are adventure hooks and modules along the way, but the main drive comes from the players, and the endeavours they choose to undertake. This picture is perhaps too optimistic (there was always plenty of bad practice around), but this is the campaign format advocated by the rulebooks. It is the main way the game was meant to be played, even if many people didn’t. If you follow the instructions on the tin, you will get a good game.

* * *

2nd edition AD&D is a different beast, an attempt to create a new, accessible set of rulebooks in place of a game that became overburdened with unwieldy and dubious optional rules and character options. It was created by a committee, although, to its credit, a committee of experienced game designers who were all old AD&D hands. 2nd edition plays safe while trying to reconcile mutually contradictory demands: to consolidate a decade's worth of new materials and popular house rules; to deflect parental and religious criticism from the game and establish it as a family-friendly brand; and to serve as a springboard for several new novel and product lines. It is the kind of compromise that people can accept, but generates little enthusiasm.

|

| Puns |

2nd edition is a "cleaned up" edition, on three levels. First, it whitewashes the moral ambiguity, earnest violence, and weirdness of the earlier game, to focus on more straightforwardly heroic character types. It is squeakier, cleaner, and yes, a little milquetoast. Assassins and half-orcs are right out in the core books (yes, they are brought back in those crappy expansion books that came later, and which only Complete Weenies used). It also reduces the specificity of the game rules: the Illusionist and Druid classes, which had had their distinct rules and spell lists, are folded into the general Wizard/Cleric character type, where they no longer stand out. The Ranger and Bard also lose a lot of their flavour. This is not to the game's benefit. The third aspect of cleanup, on the other hand, is beneficial: 2nd edition is easier to grok, has more coherent mechanics, a rudimentary but functional skill system, and a combat system that moves from attack tables to THAC0, a badly explained but ultimately quite easy formula. Crucially, though, the Main Rule is muddled: the bulk of experience is now awarded for “story awards” (or whatever they are called), with some for monsters (this has continuity with 1st edition) and some for class-specific stuff. Much less laser-like precision.

|

| A M'lady |

|

| Bad Stuff |

And that is the main difference: the playing culture surrounding 2nd edition is not simply a diluted version of 1st edition’s, but a hotbed of bad practice which will harm your games. Massively overwritten encounters, dungeons reduced to flat and boring hack and slash and “cabinet contents” design, blatant railroading, contrived attempts at forcing AD&D into game styles it can’t support well, combined with an unhealthy proliferation of character snowflakery: it is all there. You can run good games with the 2nd edition rules (we did), but you cannot become deeply immersed in 2nd edition fandom without coming away with bad playing or GMing habits (we did).

To its credit, 2nd edition, while it suffered from a horrible bloat of barely (if at all) playtested of filler supplements in its day, does have two strands of creative legacy that are worth noting. First is a sequence of campaign worlds, which, while not free from the sins of the age (bloat, sanitisation), are obviously labours of love in a way the core game really wasn't. People who remember the likes of Al-Quadim, Ravenloft, or (the best of them all) Dark Sun remember 2nd edition much more fondly than those who wanted to play “just AD&D, thanks”. The support material sucked just as much, but some of those worlds are pretty gud. (Planescape is not even AD&D, but some weirdo thing for weirdos. The less we speak about it the better.) Second, the second edition era produced a whole bunch of really good AD&D-based computer games. This success story begun with 1st edition-based games (the Gold Box series), but continued well into the 1990s, and included a whole lotta classics that still stand up today. Not all of them were great (Dungeon Hack and that one stronghold building game were godawful, and Baldur's Gate 1 is a colossal MEH), but the likes of Eye of the Beholder and Shattered Lands have stood the test of time very well.

|

| The Quintessential 2e Experience |

So that's the REALLY TL;DR take. In the end, it would be quite easy to run a good game with the 2nd edition rules (I have been in many), but if you have access to 1st edition, it just makes more sense to go with that one, and maybe adapt THAC0 and a handful of rules that you like.

Sure, call 2e “OSR”, what do I care. But it is not, and will never be part of actual old-school D&D. It is therefore * * O F F I C I A L L Y * * cast out into the outer darkness; and in that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Undersigned,

Dr. Melan, Ordo Praedicatorum & Congr. Romanae & Universalis Inquisitionis.

|

| What the hell?! |

Postscript: The New 2e and What to Do About It

Is there a purpose to this “guy between thirty and death rants about old stuff” post other than grouching and historical reminiscence? Perhaps. Actually, yes there is. There very much is. It looks like 2e is coming back, and it is now even run by another fat, woke upper-class lady like the last time.

It increasingly looks like D&D One will be shaped by very similar driving forces to 2nd edition: to consolidate a decade's worth of new materials and popular house rules; to deflect increasingly shrill political criticism from the game and establish it as a neutered corporate brand for safe and easy consoomption; and to serve as a springboard for broader monetisation as a “geek culture” property. You might easily think “surely, this will be as bad as 2nd edition”, and you would be wrong. By my inquisitorial authority, I hereby predict that it will be worse than 2nd edition in every aspect. perhaps three times as bad?

In our time, the real enemy is not so much Artpunk, which has spun off old-school gaming and really become something else. This statement should not be taken as automatic disparagement. What is called Artpunk can be done well, if done by talented and resourceful people. Even if it doesn’t create something good, at least it has a soul. However, nothing can fix the game equivalent of Corporate Memphis. Sixth edition, or what is called “One D&D”, will be a commercial juggernaut and a creative disaster. It will be the rebirth of that specific, 2e-style of corrupt blandness that outraged the OSR Taliban so much, and got them so annoyed they ended up getting off their behinds and actually doing something worthwhile.

Here is a threat

that is also an opportunity. There is creative energy in butthurt, and setting

up TRV old-school gaming as a bottom-up alternative to corporate D&D is a

rare gift whose potential should not be neglected. This section of the hobby

should of course be open to dissatisfied players who find their way here, but

it should distinguish itself as a clear alternative. The best way to do so is by

making a compelling argument for the old-school way, and cultivating excellence

in game materials, sensible playing advice, and of course through lots of actual

practice. Then, and only then, that which had once lived, and now slumbers with

the occasional grunt and growl, shall live once more and rampage anew across

the land.