Seven Voyages of Zylarthen (2014/2017)He Fights On!

by Oakes Spalding

Published by Campion & Clitherow

The list of old-school games is long, and even an incomplete catalogue shows a confusing multitude of clones, hacks, and homebrews. Most of these systems need no enthusiastic introduction, since they shall mostly entertain a single gaming group; nor do they deserve scorn for mostly the same reason. A few have met success as standard systems to play some sort of D&D: OSRIC, Labyrinth Lord, Swords & Wizardry, and lately Old School Essentials, while a few others serve a more specialised audience. The differences among systems are both impossible and useless to elucidate, since they are usually minor variations with little functional difference. You know two or three, and you know most of them.

There are a few publications in this category which are worthy of special attention, and this review is about one of them: Seven Voyages of Zylarthen, a hidden gem of old-school gaming. In this post, I will outline in more detail why this first unassuming game deserves recognition, but here is the essence. Seven Voyages is a thoughtful, in-depth reimagination of 1974-era Original D&D that operates with individually subtle changes to the rules and their interpretations, but through a multitude of small tricks, creates a coherent new game out of the smaller pieces. The end result is a legitimately interesting “alternate history” OD&D with good editing and numerous innovations which add up. On a personal level, I also consider the game to have resolved the few fundamental disagreements I have with D&D’s deeper design decisions, and done so with taste and respect for the original work.

(Note: there are two versions of the game; an original release from 2014, and a revised one from 2017. There are slight but notable differences in the attack tables, and details such as bows attacking twice but ranged weapons getting substantially nerfed.)

* * *

The Basic Idea

Seven Voyages of Zylarthen mainly builds on LBB (Little Brown Booklets)-only OD&D. Sticking to the booklets as a general principle sidesteps one of the issues afflicting other attempts at retro-cloning the original game: once you start to include concepts from Greyhawk and the other supplements, your game starts to converge towards AD&D or one of the B/X systems, losing the qualities which makes the 1974 rules distinct and coherent in their own right, and making them look like a poor, disorganised prototype of later, more complex systems. In its core rules, Seven Voyages sticks to its guns, and while it is not obsessively concerned with conceptual purity, it puts down a good, practical argument for playing this version of LBB-only OD&D on its own merits.

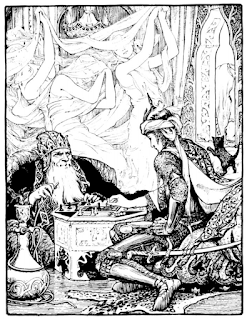

The unity of

vision is also apparent in the game’s presentation. Without being obsessive

about it, the game is well edited (something OD&D is not), written with clarity

and a sure hand that remains legible as a reference, while using just enough

flavour to give it character (something OD&D struggles with). It looks like

the OD&D booklets in its choice of typesetting and simple one-column

layout, but benefits from the hindsight and polish of the last few decades. It

also benefits from using the art of a single artist, Victorian storybook

illustrator John Dickson Batten, for its artwork. These pieces, sometimes

altered or cleverly cropped to fit the depicted concepts, but always selected

with a firm taste, are the best example of using public domain art I have seen

in a game supplement. They give Seven Voyages a cohesive feel and a peculiar

identity, they illustrate how we ought to imagine this or that aspect of the

rules, and they give the work an implied setting that is true to OD&D, but

which is also of its own.The Golden Age of Illustration

Seven Voyages has its personal voice, its own carefully selected reading list, and its own take on the OD&D setting. It is less knights-and-wizards pseudo-mediaeval and more a marriage of Sindbad-style oriental stories, Victorian fairy tales, plus a decent helping of Greek mythology and swords-and-sandals sensibilities. To this are added the works of Anderson, Burroughs, Dunsany, Howard, Leiber (lots of it), Tolkien, and Vance (plus that one Van Vogt story with the proto-displacer beast). ERB’s Mars books become an even more prominent influence here than on OD&D, based on incorporating materials from the unofficial Warriors of Mars supplement. This is a good reading list, but it is the consistent application of their repercussions through the rules which make them effective. These changes to the OD&D base range from smaller, cosmetic changes (a silver-based monetary system) to interpretations (ability scores are considered a kind of “heroic range” above normal human capabilities, the gods are limited “petty gods”) and a few fundamental changes with considerable downstream effects (radically reimagined classes, the central combat table).

* * *

Character Creation

Seven Voyages

of Zylarthen’s differences from OD&D

start to emerge at character creation. The six ability scores are rolled with

3d6 in order, but unlike the D&D lineage, these scores are understood to be

a cut above a common man’s capability; so even a 7 or 8 would represent some

sort of heroic ability. In an audacious move, the infamous female Strength rule

makes an appearance: women roll their Strength on a 2d6, but add a point to

every other ability score. Beyond proving beyond a reasonable doubt that Seven

Voyages is most based and redpilled, this rule is a useful gatekeeping test

to weed out communist furry infiltrators. Communist furries will shriek and

curse most loudly; while smart and chadly gamers will clearly realise that

ability scores do rather little in OD&D-based games, and that +1 to all of the

other abilities gives a higher probability of actually hitting the rare bonus.

It must be noted that the author himself has had second thoughts about the rule,

and in the 2017 revision, a similar optional rule goes into effect for male

Wisdom, with interesting consequences shown later. The most common role of

ability scores is in fact to give characters an XP bonus; and unless a player

is dead set to play against type (completely possible without disastrous

consequences), a +10% XP bonus is reasonably easy to obtain for just about

anyone.

|

| Congratulations, You Have Just Offended the ________ Community |

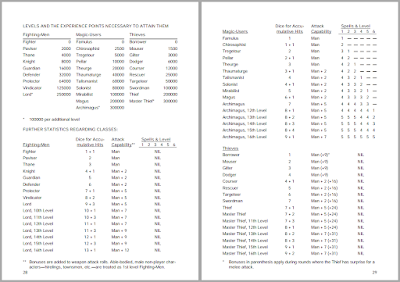

True to its influences, the game makes a large change by removing the Cleric as a playable character class, and adding a radically reworked Thief who bears more resemblance to light, lucky swashbuckler characters like Ali Baba, the Mouser and – yes – even Conan than the classical Bilbo-style burglar. We thus have a lineup closer to the norm of sword & sorcery tales. Yet even these classes are changed in comparison with their original form.

- Fighting-Men should be mostly familiar with more hit dice, faster attack progression, and the ability to use the full range of weapons and armour (this will confer advantages that we will come back to later). This is not as straightforward as it sounds thanks to the expanded combat rules, particularly thanks to the rule granting multiple attacks, but it is still the same character type.

- Magic-Users are mechanically unchanged, but their spell list (like OD&D, extending to six spell levels) is a mixture of traditional M-U, Clerical and Illusionist powers, each level offering 20 known spells. The resulting combinations make for quite interesting character types; you could play the snake-charming yogi with his cure light wounds and snake charm, the mesmerist using colour spray, dancing lights, and ventriloquism, or the traditional sleep/magic missile combat bot. The slow advancement of M-Us is compounded by their need to obtain new spells and write them into spellbooks, a costly endeavour which shall further slow down their advancement due to the game’s XP scheme.

- Thieves are an entirely new class bearing the same name. Instead of percentile skills that improve with their level, they benefit from a smattering of fixed special abilities: the ability to unerringly hide in shadows, but only if unencumbered (this means carrying almost nothing beyond a dagger); luck (allowing them to reroll, or forcing an opponent targeting them reroll one die per combat); a flat 4:6 chance to pick locks; a hefty surprise attack bonus (more later on how this works); familiarity with thieves’ cant and safehouses; and the small but useful ability to squirrel away 500 coins without incurring encumbrance.

All of these classes have fancy new level titles, and Seven Voyages uses them in a matter of fact way in the rulebooks. At first, this is funny and weird (you can hopefully tell a Thane from a Tregetour, a Mirabilist from a Mouser, and a Chirosophist from a Courser); then it becomes annoying (is that referring to a fifth-level Fighting-Man or a sixth-level one?); and finally, natural. There is a definite learning curve to it. You can also play the usual humanoids with the usual level limits As in pre-Greyhawk OD&D, Hp is exclusively rolled with six-siders, you just roll more or less of them for certain levels. Unlike OD&D, player characters do not necessarily die at 0 Hp, but roll on a random table with 1d20, with results ranging from instant death to fatal wounds, permanent injuries, serious wounds requiring surgery (this needs a 500 gp surgery kit) and/or rest, and – rarely – just getting knocked out for good.

All things

considered (and this is without the benefit of playtesting), the Thief is

lovely, but seems a bit too good to be true. While restricted in armour, they

have decent Hp and saving throws, moderate fighting ability, and a rapid

advancement scheme. A fourth level Dodger will have 4d6 Hp, the ability to

fight with most weapons save the bow, and have Thief abilities at their

disposal, while a fourth level Knight will have 4d6+1 Hp, fight with a +2

bonus, and have the ability to wear heavy armour – while reaching this level

2000 XP later. In OD&D, Thieves advanced quickly because they were fairly

weak, but here, this is no longer the case. All Zylarthen classes are

slightly stronger than the OD&D baseline, but the Thief is very strong

indeed – comparable to an elf, but with rapid advancement and no level limits. I

might be tempted to switch the progression of the class with the Fighting-Man’s

and call it a day.4:6 of Poking an Eye Out

Where advancement is considered, Seven Voyages of Zylarthen awards experience for two sources. This is an excellent choice. It adopts a minor variant of the LBBs’ monster XP scheme, which was later tossed out in Greyhawk for being unreasonably generous – this, coincidentally, makes it just right for modern campaigns, which are not 24/7 affairs. XP is awarded on a 100 x level basis, then adjusted downwards if the party is adventuring in an unreasonably easy environment (e.g. a party of 3rd level characters adventuring on the 2nd dungeon level receives only 2/3 of the calculated monster XP, but they would gain full XP for descending to level 4). The second source of experience comes from treasure spent after adventures, on a 1 silver piece = 1 XP basis (in keeping with the silver-based economy). This rule, which is essentially identical to one I have implemented in my campaigns, is a good way to remove excessive gold from the party, as well as emulating swords & sorcery tales and “Arabian Nights” style adventures – which also tend to feature spendthrift heroes who can easily blow through a large fortune and continue without a penny to their name.

Targeteer or Talismanist?

Your Life May Depend on it!

The final stage of character creation concerns equipment and encumbrance. In contrast to D&D’s mountains of gold, Seven Voyages sticks with the silver standard. Beginning characters receive their customary 3d6*10 sp, but equipment prices have been readjusted. Beginning characters will no longer be running around in plate mail (500 sp), and even mail (200 sp) or fine horses (200 sp) shall be out of their reach. Most NPC Fighting-Men in Zylarthen will be lightly armoured in the style of the Ancients, and only elite armies will be kitted out in heavy gear. Magic-Users shall receive their first-level magic book for free, but will have to spend 2000 sp per level on books for higher-powered spells.

To all this is

added a neat slot-based encumbrance system rated in dots (o). Items are rated from one to several dots, each occupying a single

space in inventory; a few will count as “zero items” for the first item and one

for subsequent ones (e.g. dagger, a set of clothes), and tiny ones will incur

no encumbrance at all. This is all rated on a 1-20 scale depicted on the

character sheet, and filled up as you go, from unencumbered (0-5 o) to light (6-10 o), medium

(11-15 o), and heavy (16-20 o) – with consequences for movement and other activities. Since even

a shield is ooooo and mail is ooooo o, and weapons tend to go from oo to ooooo, carrying items and loot will be a major consideration during play.

Thieves, in particular, will need to travel lightly, especially if they wish to

hide in shadows. They may wear leather (o) with a helmet (o) and

carry a buckler (o) along with a sword (o), but this leaves a single slot to stay “unencumbered”, or six to stay

light. This is not too easy to do with dungeoneering gear. (Notably, the Reference

Sheets include 18 ready-made equipment packages you can roll for on a

class-by-class basis.)

|

| Two Third-Level Characters |

Combat and Magic Rules

Seven Voyages adds a more complex combat system to OD&D, and implements a radical innovation in combat resolution. Instead of an attack chart broken down by level and AC, all PC and NPC attacks are conducted on a weapon vs. AC matrix. This was a central mechanic in Chainmail, but was only brought back for D&D in an awkward fashion – something for the hardcore pocket calculator types. Well, there is nothing complicated about this table: the simple genius of it is that you roll your d20, add your class-based modifier if any (this is the “Man +2”, “Man +5”, etc. of the character advancement table), and look up on your character sheet to determine which targets you will beat. As easy as pie, and it introduces a nice difference between weapons: spears and polearms are very useful against lightly armoured opponents but less so against armoured ones, while maces, hammers and battleaxes can crack plate a tad easier than a sword. There are further differences:

- Weapons are ranked by “weapon class”, from 0 (unarmed) and 1 (dagger) to progressively longer implements like spears (10), polearms (11) and lances (12). This establishes initiative order in a double fashion: a man with a spear shall attack a man coming at him with a sword before his foe can reach him, but this advantage will not be in effect in subsequent rounds when the fighters have closed in. In fact, if initiatives are tied at this point, the man with the smaller, quicker sword can stab the spearman before it is the spearman’s move!

- While all weapon damage is 1d6 by default, some get a -1 damage penalty vs. large opponents (daggers, axes and bludgeoning types), and some get a +1 bonus (longswords, spears, polearms and lances).

- Weapons may be broken on a natural 20, or when slaying a powerful or heavily armoured opponent (this is a simple saving throw based on item cost and the opponent’s armour – yes, that spear will break on you, so make your spear-carrier bring a spare or two).

- Finally, weapons have a frontage in feet needed for effective use, limiting the number of combatants per rank (daggers, axes, spears and smaller swords require 3 feet, maces, longswords and hammers 5-5, and the mighty battleaxe and morningstar need 10).

- Missile attacks are governed by slightly different rules. In the first version of Seven Voyages, they may be fired once per round; and in the second, they can be used twice, but they are harder to hit with, and plate is essentially impervious to missile fire by anyone except a 7th level or more powerful Fighting-Man. In either version, archery must be declared at the start of the round like spellcasting, prevents movement (except for Elves, who can “move and fire” in the Chainmail fashion), and may be disrupted by successful hits.

This is the gist of the basic combat procedures, but Seven Voyages introduces a handful of more complex optional rules and special cases, from disarming or driving back a foeman to handling fire and pots of burning oil. These are well-considered, reasonably simple, and useful to add to a campaign. Some of the more interesting ones are…

- Critical hits, rolled on a natural 20s, will inflict two dice of damage, but a weapon break roll is called.

- Extra damage dice may be added at the price of a -5 attack roll penalty each. This makes sense of the Thief’s +9/+16/+24 surprise bonus: it allows a Thief to strike surely, or inflict several dice worth of damage with a sure hand.

- Mounted combat gives +2 vs. non-mounted opponents, and +4 when charging – reflecting how useful horses can be on the battlefield.

- Multiple melee attacks are possible against grouped opponents with a lower HD – one per HD of the attacker, up to four. This rule may not be combined with extra damage dice, but it makes Fighting-Men particularly effective (even Magic-Users can also take advantage of it from level 3, if they are particularly reckless).

- Helmets are struck on any unmodified 7, and any character who is too stupid, too poor, or too Magic-User to don one, will be struck automatically with an extra damage die. Ouch!

- Shields (and M-Us’ staves) may be sacrificed to block a single successful strike before damage is rolled. Thieves’ bucklers, which otherwise grant the same protection, are not useful for this purpose.

- And yes, there is Turning Undead. As Seven Voyages has no Cleric class, any character may attempt to turn undead creatures by presenting a true holy symbol. Except… the Turning Undead roll is modified by high and low Wisdom. If you will remember, men in the 2017 version of Seven Voyages of Zylarthen have only 2d6 for their Wisdom roll, so as a cascading effect, there is a very good probability your all-male adventuring party will not be turning too many critters above the ghoul/shadow level.

Magic in Seven Voyages is reasonably close to its OD&D antecedents. As mentioned before, Magic-Users will need to expend considerable effort on obtaining spellbooks (each of which may hold 12 spells of a given level), and filling them with new spells. The game covers six levels of spells, combining the Magic-User spell list with some additions from the Cleric, and even a few from the AD&D Illusionist. With 20 spells per level, this is a decent selection, and returns to OD&D’s cleaner idea of magic where the likes of teleport, disintegrate, geas and stone to flesh represent the apex of spell power. Still, I must confess a slight dissatisfaction: where the game was bold in moulding most character rules to its intended tone and assumed setting, the spell list is rather bare-bones. We have the perennial favourites, but not much in the way of new, colourful stuff. It is a decent baseline, but not more than that.

* * *

Monsters and Treasure

Before Greyhawk and the other supplements, D&D was a game with a very different menagerie than we now recognise. Nowhere are found later dungeon favourites like the beholder, the owlbear or the rust monster; some, like gelatinous cubes, are only referred to as possibilities, while insects and animals are left to a single vague description noting that “These can be any of a huge variety of creatures such as wolves, centipedes, snakes or spiders.” (OD&D, vol. 2, p. 20) The bestiary is therefore a mish-mash of Tolkien creatures, monsters from classical antiquity and British folklore (but almost none from mediaeval bestiaries except the gorgon and the cockatrice), standard undead, and a few slimes, goops, and blobs. How a LBB-derived game builds its own monster roster is therefore a very interesting dilemma.

Stalking U

Seven Voyages picks and chooses from the expanded OD&D and AD&D roster,

but does so by putting its own stamp on this eclectic bag of material. Here, Mr.

Spalding works magic with seemingly familiar ingredients and a little editing:

much of what you see will be known D&D fare, but there is often a neat

trick or small flourish that adapts the monster to the game’s implied setting. Consider

the monsters which could not be included in the rules under their proper name for

legal reasons. They are still there, but new: we have the dreaded phaetonian, “a

rare and sometimes extremely malignant being, native to the planet Jupiter, […]

a levitating mass of pseudopods and eyestalks, framing a huge central eye”

(this surely describes a sordid creature from a less known Greek myth), shift panthers

“shifting” electromagnetic waves and attacking “out of an ever-present

hunger to devour a protein substance usually found only in bone marrow”

(inspired by the Van Vogt story), tentacle men “rumoured to live in

inaccessible ancient communities many miles beneath the earth”, or solians,

“native to the interior of the Sun but sometimes encountered in the deepest

depths of the earth”, terrible winged beings which are only coincidentally

identical to OD&D’s balrogs in their statistics.

Then, a second group of monsters are adapted from the game’s main source materials: there is a whole procession of Barsoomian imports, from thoats and banths to the intelligent Martian species (including a few of their radio-era technological devices – radium pistols, disintegration rays, mechanical brains, and the like). Robots and androids, mentioned but never actually described in OD&D, make an appearance in their pulp era “mechanical men” forms. Gods and goddesses are described in a very D&Dish mixture that takes a little from Babylon to the Kalevala (although not given stats – the entries describe their potential behaviour in a game campaign). These divine beings are fallible and flawed “petty gods”, and the game leaves open the possibility of a greater Creator existing above them all (this theory was quite widespread among the educated classes of classical Greece and Rome).

We find some odd

decisions I am still ruminating on. The game’s general rules are consistent in

using a d6 HD and damage die (some larger monsters of course do multiple dice

of damage), but in the Book of Monsters, the rule is broken multiple

times: undead roll d12s for Hp, lycanthropes roll d10s, and Martians roll d8s. This

is a deliberate choice, and fairly weird, since some undead then have their HD

reduced – skeletons and zombies are ½ HD, wights and wraiths are 2 HD – but some

don’t, as mummies are still 5+1 HD, and vampires 7 or 9 – rolled with

twelve-sided dice. That is just brutal, especially when you WILL fail to turn

them due to your low Wisdom (see above). Then there are important adjustments:

monsters are all assigned a correct AC that matches up with the way they would

be armoured, and not just in the sense of “stronger critter = better AC”.Roc On!

(Not Even the Last Fight On!

Themed Joke Here)

For all the work on the monsters, nowhere does this volume deliver good stuff better than in its treatment of human NPCs. D&D’s well-known “man types” are supplemented with Vikings, amazons, assassins and, most crucially, soldiers of various troop types and compositions. This is a very useful entry, outlining differences between, say, peltasts, Varangians, koursors and turcopoles (troop types which give the game a great flavour), with their typical equipment, organisation and morale, and adding a quick table to see how the army is currently faring, whether it is a friendly or foreign force, and whether they are hostile towards the surrounding countryside, and, thus, the party.

- For example, we may find ourselves face to face with hoplites equipped with spears plus swords or axes, wearing mail and shields, consisting of 500 men, with a morale bonus of +0, currently victorious, and (since we are in the wilderness) being a foreign group who are not currently hostile.

- The next military group, then, will be a mixed force of three types: 160 irregulars (they will only carry spears, various small arms, and wear leather with -1 to morale), 120 crossbowmen (crossbow, sword or axe, leather, +0 morale) and 240 turcopoles (mounted crossbowmen, also equipped with shields, +1 morale). They are on an exercise, a foreign force, and not hostile.

We also have a type affectionately and aptly called “Evil Men”. Most Evil Men are just character types allied with Chaos. Here, we have the initially dubious-sounding pleasure of relearning those level titles, which once again shows that this is a based and redpilled game for true connoisseurs. It would not do to call an evil fifth level Fighting-Man a Defender; no, he (or she) is in fact a Rakehell, on his or her way to becoming a Villain! Likewise, the party Thief will be a Sicarian (but not yet a Phansigar), and the Magic-User a prestigious-sounding Hecatonarch. Better learn these, because they will be referred to on the encounter charts in Volume IV.

However, the most fascinating part is undoubtedly the section dedicated to NPC spellcasters. As it has been mentioned, Clerics were removed from the roster of playable classes, but they are surely found in the adventures? This is indeed the case, and they are not given short shrift – along with Druids and Witches, they receive their own specific powers. It is all very creative, and here is how it goes:

- Evil High Priests or Priestesses (as well as their Lawful counterparts) are not spellcasters per se, but they receive around two to four formidable powers. For example, Thromekthes, 8th level Evil High Priest of The Spider God, will have laser eyes and wind walk; while Iomene, 13th level High Priestess of Artemis, shall have commune, mass hypnosis, and weather manipulation. Regular priests are not spell-casters, just powerful men with 4 HD and an aura of divine favour.

- Druids are “priests of a savage nature religion”, casting Magic-User spells, as well as having the ability to turn into small animals.

- Witches are ridiculously high-level relatives of the giants, possessing a dangerous magic staff only they can use, with good odds for a crystal ball as well. They have their own power list, including formidable things like indefinitely controlling the seasons within their domain, ensorcell a major item, or vanish/appear familiar places where and when they please.

These, alone, make the game’s second volume worth the price of admission.

Fewer good

things may be mentioned about Volume III. As already discussed, the player

spells are decent but not special. However, it is the magic item section where Seven

Voyages drops the ball. This, I think, is a blemish on an otherwise very

imaginative and thoughtfully constructed game. Not that the treasure section

does anything worse than a competent LBB clone with a bunch of additions from

the supplements and the advanced game, or that its magic item selection is poor

– the problem is that it does not do anything more, which we might have

expected from the previous materials. Perhaps age and too much familiarity with

eyes of charming, horns of Valhalla and horseshoes of Zephyr have

made us cynical. But this was a great opportunity for more exotic fare dreamed

up by the author, and the opportunity was not exploited – more’s the pity.Fight O... ooooh NOOOOO!

* * *

Campaign Building

The game’s final volume is a relatively slim one. It is not a full treatise on constructing and managing Seven Voyages of Zylarthen campaigns, and leaves out some of the flourishes found in OD&D (castle construction, ship-to-ship warfare, and airborne combat are omitted). However, it is a decent collection of tools and instructions for setting up a campaign, while also pointing to further useful material (Philotomy’s Musings and A Quick Primer for Old-School Gaming – Wayne Rossi’s Original D&D Setting, another contender for inclusion, is mentioned in the appendix).

Guidance for adventures in the Underworld follows the good advice of the LBBs, and gives concise but useful instructions to make good dungeons. (A sample level, and the relevance of level connections illustrated on a sidecut connection map might have been nice.) It retains OD&D’s focus on doors being stuck and hard to force open, something that adds significantly to gameplay. It also provides sensible falling rules for pits: while shallow ones will not kill a character, deep pits force a save vs. death for every 6 Hp of damage to avoid breaking a limb.

The dungeon encounter charts use the “dipper” approach of OD&D, where monsters drift up from the lower level charts, although instead of the original game’s six depth levels (which could soon get very nasty), we have twelve, with a bit of a cushion. Thus, the Level 1 chart will have monsters from charts A, B, C (these are relatively easy man types and lesser monsters), 1 and 2. By the time you are down to Level 5, you can meet 7th level monsters like elephants, basilisk, mummies, and white apes. The tables are in the general well done, with good variety (this is an underappreciated area of game design, but one which needs pointing out), and theoretically includes Gods and Goddesses on the lowest levels.

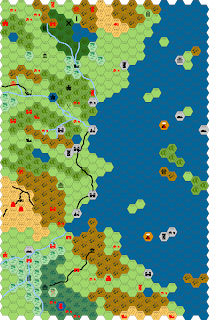

Wilderness rules

are basic in the 2014 version, and much expanded in the revision. Movement is

conducted in 30-mile hexes (very much unlike the “OSR standard” six-mile hex,

or the five-mile hexes used in OD&D), and, in the revised version, follows

an interesting dice-based system. To be able to enter the neighbouring hex, the

party must roll under their adjusted daily movement rate with an 1d20, or they

will remain in the hex for the day. The basic rate will be 10, first modified

by mounts if they are available (camels add +3, ponies +4, and light horses

+7), then adjusted by a multiplier derived by the terrain type (roads and clear

terrain allow full movement, the likes of woods and deserts cut movement to ½,

and swamps or mountains to 1/3). Weather conditions further cut down this rate:

great heat and heavy rain to 75% of the previous value, light fog or snow to

50%, and a blizzard or torrential rains to 25%. That is, your company mounted

on light horses might start with 17 points, but passing through woods would

reduce this to 8 – you may be able to travel to the next hex that day, but it

is more likely it will take two days, or even three if you are unlucky, or if

you are forced to hunt for food (-2 modifier). One risk here is that without

provisions, the characters will soon gain dots of “virtual encumbrance” at a

rate of oooo per day without food, and oooo oooo oooo (yes, 12 dots) without water, which may be reduced with a

successful adversity check to ooo and oooo oooo, respectively (and then you just die at 35 dots). There is an

interesting “man vs. nature” mini-game here that’s not usually a part of

D&D, compounded by particularly brutal odds of getting lost on unfamiliar

terrain. The whole system is also applied to air travel (riding a hippogriff or

a giant eagle is the gentleman’s choice) and various ship types, which are

affected by wind strength and direction.Less Complicated Than

it May Seem!

A good set of

outdoors encounter tables (which are reasonably cross-pollinated, e.g. rolling

on the “Arid Plains” table sometimes throws in a group of “Flyers”, or

something from the nearest different terrain type) is then followed by a

section titled “How to Create a ‘World’ in Under an Hour”. This is,

essentially, a methodology for setting up wilderness sandboxes, with a focus on

creating a fun map conductive to adventure... by exploiting a random generation

function in Hexographer, and

then adjusting to fit. While it is tied to a legacy version of a specific hex

mapping tool, this is a fun mapping method you can mess around with at More Than an Hour

Well Spentwork

home while setting up your coastlines and islands, placing forests and mountain

ranges, and finally peppering it with points of interest, but in no way does it

take “under an hour”. My effort, at least, lasted about a long evening, until I

feel into my bed, dead tired but reasonably happy about what I have wrought.

The booklet concludes with a section on monster languages. This aspect of play receives unusual attention in Zylrthen’s rules, down to establishing language families which are an entry noted in the monster stats. You have the common “Type A” language, then more specific families such as the Barsoomian “Type B”, elemental languages (“Type E”), a type spoken by dwarves, elves, goblins and treants (“Type M”), and even “Type J” languages, referring to isolates and minor alien/lost languages which are not spoken outside a very small circle. This is a quite obscure area from my perspective, but obviously done with a lot of thought – so, if languages are your thing, this is a variant worth considering.

* * *

Supplement I: The Book of Spells

I would be remiss not to mention the game’s first, and to this date only supplement. This addition came out in 2017, and makes an effort to double the number of spells in the game from 150 to 296, and “to continue the process of “re-imagining” the original fantasy adventure game”. This was not a good idea. Certainly, this booklet adds “more stuff”, mainly by plundering the Druid spell list and extending the Magic-User spell range to 9 spell levels. But it does not really add to the imaginary range of Seven Voyages; it does not make it more distinct and rich – in fact, it makes it weaker.

The real strength

of the game is found in working with a consistent LBB-based framework and exploiting

the possibilities of this system. The rules carefully weighed what to

incorporate and what to leave out. Supplement I, like OD&D’s Greyhawk,

leaves behind the consistent and neat world of a tightly designed game, and

starts to look like a game with bolted-on bits. In OD&D’s case, this was the

beginning of the road towards AD&D, but for Seven Voyages, there is

no compelling reason to move in this direction. A six-level spell system, just

like a 9- or 12-level advancement system, is neat: it sets a sensible barrier

to the accumulation of power, while letting players reach that level over the span

of a long campaign. Self-contained, closed-end advancement systems close a can

of worms that was opened with Greyhawk and then never properly addressed

until Ryan Stoughton on ENWorld developed the E6

variant. While some character might realistically hope to aim for disintegrate

and invisible stalker, nobody will ever reach the level of power to

cast enchant boats or the white puff ball spell, and for NPC Arcimagi,

we do not need a spell to describe how they enchant a boat – they just do.Don't Fall For This One

The Book of Spells, therefore, is not something that was really needed, and I seriously doubt it really adds much to the game. Although… it does expand the list of High Priest and Witch powers, from 12 and 20 to about 40 each. These may be useful to consider for your campaigns, but I would not add the rest. The lesson is eternal: if something is already very good, it is better not to mess with it. Seven Voyages of Zylarthen does not need to grow in this direction. What is Campion & Clitherow up to? Mr. Spalding has published an Almanac of Fantasy Weather, probably a useful utility product if you are very deep into climate models, but no adventures or setting material for the game have seen the light – and more’s the pity.

* * *

Conclusions

As it may be apparent from this long and detailed review, Seven Voyages of Zylarthen has struck me as an excellent old-school game, and precisely the kind of release that old-school gaming needs. It is something that builds on the rich traditions of gaming with respect, yet with a powerful vision to personalise it; it is funny and charming where needed, and intelligent in its re-imagination of the LBB rules. It lets the original game shine with a new polish. Of course, it does not replace it, and it may be that you will need a healthy appreciation of the OD&D spirit to appreciate it to its fullest. Certainly, the broader “OSR” has barely acknowledged its existence, and that is no accident: this is really a game of another time, belonging more to the Fight On! and Knockspell era than what came afterwards. It is not without flaws or rough edges, and it is the definition of niche.

However, Seven

Voyages of Zylarthen wins on its strengths, and what a glorious victory it

is! It manages to recapture something, something of that elusive playful

spirit and infectious imagination that you can see in OD&D. If you are an

old hand at playing D&D, Seven Voyages is different and distinct

enough to feel like a new game, or to let you view the original game through

a different lens, and to gain newfound appreciation for how elegant it

is under the bad art and worse editing. This is D&D fantasy by way of

Sindbad and brass cupolas, glittering seas and Harryhausen-style Greek myths,

depicted through the repurposed illustrations of a Golden Age illustrator. Yet

it is not a mere question of exploring a set of aesthetics, but craft: imaginatively

modified (or just skilfully selected) mechanics supporting that vision, and

going all the way to make it happen. It can, therefore, be cherry-picked for

good ideas (and it has plenty), but it is the whole that truly makes it

excellent. And remember: one man, Oakes Spalding, fixed weapon vs. AC, which was

written off first as complicated, then as outright

broken. That deserves respect.Why, yes, this OSE game looks nice...

But have you heard of Seven Voyages?

This is, obviously, not a playtest review; but I intend to remedy this with a campaign later this year, as I see these rules as uniquely suited for the world of Fomalhaut (with a few house rules); as they would also be excellent for the Wilderlands, Lankhmar, Planet Algol, or some similar sword & sorcery setting. Bring it on, and let’s not forget: that Wisdom score is rolled with 2d6, no exceptions and no excuses.

This publication credits (at least some of) its playtesters, who seem to be the author’s children, in the dedication. Sweet!

Rating: ***** /

*****