|

| ...very pleased to meet you |

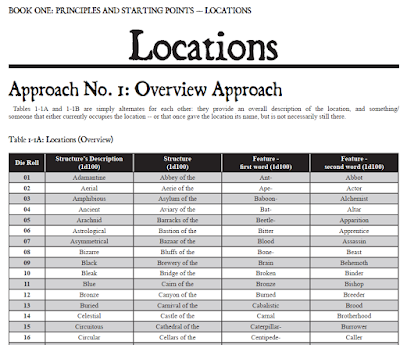

It would take long to sing the praises of the great ToAD, this modern classic of utility products, so let it suffice that its over 300 pages of tables is an inexhaustible mine of what the author, Matt Finch calls “deep creativity” – half-formed idea fragments which emerge into full-blown game material. Like Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu, its treasures are endless. Someone in the middle, there is a four-page 1d100 table for the generation of random thrones. There is enough in that table alone to create and stock The Dungeon of Thrones, if you wanted to. That’s the kind of book the ToAD is. But there, among the tables for “complex architectural tricks”, “corpse malformations”, “religious processions and ceremonies”, and “mist creatures” – which I am sometimes using – there are some that come up all the time (such as a table collection for generating individual-, item-, location-, and event-based missions), and one that is beyond useful. And this is actually the first table in the book: the “Locations (Overview)” table.

|

| The Locations Overview Table |

- Moaning Chapterhouse of the Bat-Sorcerer

- Collapsing Edifice of the Many-Legged Burrower

- Dilapidated Castle of the Bitter Apparition

- Aerial Cliffs of the Hyena-Keeper

The Wilderness Workhorse: Muddle’s Wilderness Location Generator

Yes, this is an internet tool, and you can try it for free, so go ahead. The ToAD, exhausting as it is, is not much focused on wilderness play, and its tables in this section are cool but just not as varied as the dungeon chapter. Muddle’s wilderness table is a good alternative. It combines nouns and adjectives into a list of 50 locations for your wilderness adventure. A lot of these results will be irrelevant to your current project, but you can check these and delete them, then replace them with a new batch of entries, repeat until you have the precise 50-entry roster you need. Here are the first few from the selection I got this time:

- Deep Hills of the Elder Piller (sic)

- Mausoleum of Adamantite Drows

- Dreary Treasury

- Inner Tomb

- Skeletonelder Hole

- Slimefist Tower

A lot need to be weeded out (I have developed a soft spot for Awful Peak, it is staying), and the vocabulary is much more limited than Mythmere’s thesaury (Sorry! Sorry!), but it is quick, cheap, and often does its job. You can use it to build. Deep Hills of the Elder Pillar sounds like the place where people possess a lot of good ol’ folksy wisdom, much of it involving goat sacrifice and non-euclidean things, Dreary Treasury is a place offering an interesting internal contradiction, and Inner Tomb either lies deeper in the wilderness, or it is a tomb with a hidden sub-section. And we have a cultist hideout at the end, I believe.

But that’s not all! Muddle’s set also has a dungeon room generator that’s almost as decent, and you can force it to select by theme. The other tools are less useful, although the deity generator might make Petty Gods a run for its money (Grundermir Ratvoid, Dread Fiend of Bad Breath; Malumdrim Biscuitfinger, Queen of Ants; Asheeltrym Grumblespoons, Lord of Bannanas (sic); Mulelroun, Godess of Apples; and Grelderthul the Beautiful, Queen of Aggression is certainly a pantheon).

* * *

The Implied Setting: Outdoor Random Monster Encounter Tables (AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide)

In the book that has everything, everyone will find something. Gary’s magnum opus is less methodical guidebook than an occult tome that teaches you, the fledgling DUNGEON MASTER, that horizons are infinite, and the true scope of the reaches far beyond a few narrow possibilities. Last evening, we looked up its advice on underwater combat after two characters fell into a deep pool inhabited by a water spider, and I am sure the “how much damage will I take in my armour type if I transform into a specific lycanthrope type” table has been useful to someone, somewhere – at least once in history.

When the DMG’s readers are asked which is the most important section in there, the teenage munchkin will say “Of course it is the magic items table! Here, have a vorpal mace and two Wands of Orcus!”. The journeyman will point to the dungeon dressing appendix – it is useful indeed – and the old-schooler will at once point to Appendix N for its listing of AD&D’s thematic roots, which we all know is better than the stupid dreck everyone else is reading. The connoisseur of obscure gems will note the “Abbreviated Monster Manual” from Appendix E. Bad people who need to be put on a watchlist will cite “the Zowie Slot Variant”. These are not bad answers, but for my pick, I would go with Appendix C, AD&D’s outdoor encounter system.

Random dungeon dressing and treasure tables help you fill your rooms, and Appendix N will help you develop a refined taste in genre literature; Appendix C gives you the most practical tool for AD&D’s implied frontier setting. We can appreciate the points of light concept because it gives us our points of light in the practical sense – not as aesthetic, but also as practical procedure. Random encounters, particularly when also used to populate wilderness areas, as in a hex-crawl, give you the gameplay texture to make expeditions in the outdoors varied, fun, and very hazardous. That is, they give you the everyday reality of travelling between two points on the landscape. Here is an expedition of six encounters moving between two cities separated by plains, then hills, a stretch of forest, more hills, marsh, then plains again, assuming one encounter occurring on each stretch:

- Plains: Men, nomads (150), with 13 levelled Fighters between 3rd and 6th level, a 8th level Fighter leader with a 6th level subcommander, 12 guards of 2nd level, plus two lesser Clerics and a lesser Magic-User. Assuming the nomads do not force you back in town, or just take you as captives, we can move on to…

- Hills: Elves (140), with 10 levelled Fighters of 2nd or 3rd level, 3 Magic-Users of 1st or 2nd level, and 4 multi-classed elves (4/5 level, plus a 4/8 leader). Let us not consider the giant eagles in their lair – the elves are bros, anyway. We share lembas and move on.

- Forest: 2 Giant weasels, which are 3 HD creatures. Luck was with us, unless the encounter occurs by surprise, since giant weasels suck blood at a rate of 2d6 Hp/round. They have no treasure, but their pelts are worth 1d6*1000 gp, each enough to hire 100 porters for 10 to 60 months of work, or an army of 50 heavy footmen for the same time span!

- Hills again: 16 Wolves, the basic unit of fantasy wildlife. They are 75% to be hungry when you meet them. Of course, they are hungry this time, too.

- Marsh: this is a great place to meet a beholder, catoblepas, or other high-level monsters, but instead, we get Men, pilgrims (60), 9 Clerics of 2nd to 6th level, and a 8th level Cleric with a 3rd to 5th level assistant. There is 60% of 1d10 Fighters (random level, 1st to 8th), and 30% for a Magic-User of 6th to 9th level, but they are not here right now. Still, these badasses are travelling in the world’s most dangerous terrain type except mountains. Don’t screw with.

- Plains again: 1 Huge spider, which is a good roll on 1d12, and fortunately, it is not the calf-sized 4+4 HD type, but the dog-sized 2+2 HD type. The only downside is that they surprise 5:6, which is a bad value, considering their poison is deadly.

|

| Just a random encounter, bro! |

After

this trip, you start to appreciate those sexy harlot encounters in the city (and

hope if it comes to worse, it is 8th to 11th level

Thieves out for your purse, and not a Weretiger or a Goodwife out for your

blood), and you start understanding why those points of light remain points,

not larger blots, or why those pilgrims travel in groups of 10-100. It also

puts your mind into a different frame than level-balanced games with random

monsters numbering in the 1d4 or 1d8 range. You can’t fight all those roving

death armies, and besides, it does not pay (weasel pelts excepting). You learn

to scout, you learn to run, you learn to leave behind food to distract your

pursuers (this scales up from rations to pack animals and fellow adventurers –

as the great Grey Fox once shouted back to a companion stuck in a bad situation,

“What ‘party’? The party is already over here!”), bribes of gold or good,

old-fashioned bullshitting to tip over that reaction roll. You learn to grovel

before that dragon, planning future revenge. You learn to plan an ambush to

plunder that lair you just discovered, and carry away the best valuables. Welcome

to the AD&D World Milieu!

* * *

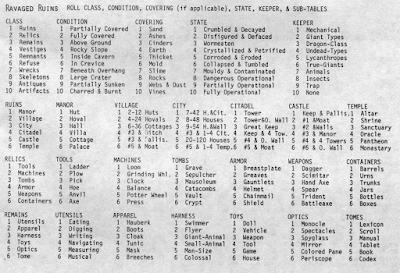

The Chad Sword & Sorcery Milieu: Ravaged Ruins (Wilderlands of High Fantasy / Ready Ref Sheets)

So

you got to know Appendix C, and suddenly gained a new understanding of

AD&D. You are on a different level. Here is where it gets stranger. From

the OD&D era, Judges Guild’s Wilderlands setting presents a truly bottom-up

sandbox setting of minimal detail and high weirdness – recognisably D&D

fantasy, but more “Appendix N” and Frazetta than the comparative classicism of Greyhawk

or Steading of the Hill Giant Chief. The “High” in Wilderlands of High

Fantasy might stand for something else than “Tolkienesque” here, even

though the setting also has a generous helping of Tolkien pastiche – right next

to old-school Star Trek, classical mythology, pulp fantasy, and Dark Ages

Europe/Near East mini-kingdoms. It is just general fantasy enough to kick you

out of your comfort zone when it turns out the Invincible Overlord has captured

a stray MIG fighter, or that the dungeons under Thunderhold, castle of the

Dwarf King have half-buried railway tracks and a gateway to Venus on their

fourth level. The described Wilderlands is filled with odd, short idea

fragments and juxtapositions, a few throwaway lines like

Wilderlands of Highly Awesome

- “Villagers charged with a centuries old oath to the ‘King of the Lost-Lands’, maintain an eternal bonfire atop a crag to warn ships off the hidden reef.”

- “In a well hidden crypt is a ring of Brathecol, one of the kings of old Altantis. (sic – ‘Altanis’ vs. ‘Atlantis’ is one of the strange ambiguities of the setting)) A stone golem is guardian of the crypt which appears as a monolithic block of limestone.”

- “The crystallized skeleton of a dragon turtle is buried on the sandy beach. The skull houses a giant leech.”

However,

there is also a procedural Wilderlands that lives in its weirdo random

tables and guidelines, which were collected in the supremely fun Ready Ref

Sheets, Volume I (no second volume was released, but the first one is a

great look into OD&D, and remarkably easy to obtain). Here you can find

rudimentary rules for taxation, trade and mining – but the most useful table is

the self-explanatory Ravaged Ruins. This table generates wilderness locations

to scatter across your hex maps, and let your players wonder about the fallen

glories of past ages – something that already establishes one of the major

themes of the Wilderlands. The table is relatively small, a simple two-pager

with results drawn from archaeology... at least at first glance. It generates a

basic ruin type, with nested sub-tables to determine the specific subtype –

there are not that many results, but the number of combinations is at least

decent. Supplemental columns also establish the condition of the ruins, their

covering (definitely archaeological in sensibilities), state, and the monsters

guarding the ruin. And it gets weird, as seen in these six rolls:

- Statued fountain, found in a large crater, covered with vines, crumbled and decayed, protected by lycanthropes.

- Bones, above ground and covered with slime, partially operational, no guardians. (What does partially operational mean in the case of a bone pile? Mediocre Judges will frown and reroll. Superior Judges will find an explanation. Perhaps this is a bone mine of extinct creatures, still excavated by locals as trade goods or building material? What of the slimes?)

- Sea-horse carriage, partially sunken and buried in a thicket, dangerous operational, protected by insects.

- Periscope inside cavern, covered in rocks, collapsed and tumbled, mechanical guardians. (Wait a minute! We are not in Middle Earth anymore, Bilbo!)

- Man o’ War inside cavern, dangerous operational, protected by trap. (It has to be a fairly big cavern for that… and what if we roll it for a place far, far from a sea coast?)

- Asphault (sic) road, partially covered in thickets, corroded & eroded, protected by giant types. (So this setting has old, overgrown, eroded asphalt roads.)

|

| Ravaged Ruins |

Not

every great table is enormous, and this one is just a throwaway

forum post by korgoth. However, The Table of Despair is a great gameplay

innovation, and a high achievement of old-school design. It becomes useful when

the characters don’t get the hell out of Dodge before the curtain falls; when

someone is separated from the main party for longer than healthy, or when

someone flees in blind panic. You roll on the table and weep, mortal. Those are

not great odds – in fact, they are downright crummy odds – but this is Jakkalá,

and they may in fact be the best odds you can get. All that for a fistful of

káitars!

|

| The Table of Dessssspair! |

Aside from its chuckling evil glee, the table communicates the danger of the Underworld very clearly. The results are appropriate, and should be pronounced in a booming, hollow voice. It is not applicable to every campaign, and it is a bit repetitive, but it is a work of simple genius. I have included a milder variant in Castle Xyntillan (“The Table of Terror”), which is derived from Helvéczia’s “Through Branch and Bush”, but all of these trace their lineage back to korgoth’s now classic post.

* * *

The Equation Changer: Party Like it’s 999 (Jeff’s Gameblog)

Curiously,

very little of the definitive old-school gaming blog has seen print; Jeff

Rients just wrote tons of material he gave away for free. And 2008 was a great

year, even by the Gameblog’s standards. These carousing guidelines

are not radically new, since they build on older principles which go right back

to Orgies, Inc. (The Dragon, 1977) and even Dave Arneson’s First

Fantasy Campaign (Judges Guild, 1977), already in vogue by 2006-2007. But

Jeff’s take is the iconic, recognised version; he was not there the earliest,

but he was there the mostest. It is simple: at the start of every session, you

can just throw away a bunch of gold pieces in wild parties, and earn the same

amount in experience points. There is, also, a random table to add risk and

complication to the downtime activity. The party may have just been looking for

some good fun and easy XP, but a few bad rolls later...

- Brother Otto wakes up with the hangover from hell, cramping his spellcasting.

- Nick the Knife accidentally burned down the inn, and everyone in town knows.

- Sir Wullam wakes up and finds himself with the symbol of the Brotherhood of the Purple Tentacle tattooed on his... oh no! Oh nooooooo!

- Sorceric has a minor misunderstanding with the guards, and is hauled in for six days in the lockup.

|

| At least this inn is not on fire, RIGHT, Nick? |

The carousing rule inverts D&D’s core equation, the 1 gp = 1 XP rule. Here, you do not gain XP for treasure you find, you gain XP for treasure you spend. AD&D’s model – which, mind you, works great, although for different reasons – hoovers up excess gold from the campaign through training costs (most of my current Hoard of Delusion party is stuck at their current level, having the XP but not the gp for training), and introduces the strategic dilemma – do we spend it on advancement or other useful stuff? It is also quintessentially 80s action movie – our hero, experiencing hardship, goes to the gym or the old karate master to bulk up for the tougher challenges coming his way. The inverted model removes money through living it up through excessive partying. OD&D’s upkeep rule is a predecessor (1% of your current XP total per arbitrary time period), but Jeff’s carousing table turns it into a mini-game and a source of new mini-adventures. You can also see Ffahrd, the Grey Mouser or Conan doing this, more than them learning new moves under the watch of a wise old instructor. Of course, it is just a table of 20 entries, with a comical aesthetic. But it is a hell of a beginning. I have my own 64-result downtime complications table from the Helvéczia RPG: here are four results for late 17th century picaresque adventures:

- One of Father Gérome Gantin’s noted enemies has vanished from town, and everyone is eyeing him suspiciously.

- Bettina von Vilingen, the noted scoundrel, finds herself the elected mayor of a tiny podunk village.

- Sebastiano Gianini, Bettina’s partner in crime, has indulged in sins better left unmentioned, and loses 3 Virtue.

- Domenico Pessi, retired mercenary, survives a close encounter with Death, but to correct the mistake, the Grim Reaper is once more on Domenico’s trail...

*

* *

The Dipper: The Monster Determination and Level of Monster Matrix (OD&D vol. 3)

For our final table, let us return to the roots: OD&D’s random monster chart. OD&D has often been called badly designed (and until its mid-2000s revival, it was mostly considered a historical footnote), but what it is is badly written, and barely if at all explained. The design itself, taken at face value instead of handwaved or second-guessed, is surprisingly tight – blow the dust off of the covers, and you find yourself something that hangs together quite well as a game. We have already mentioned AD&D’s wilderness encounter charts – here is a simple, elegant and universal matrix for running expeditions into the Mythic Underworld.

The

matrix cross-references level depth – the basic measure of zone difficulty –

with a 1d6 roll to select a random chart, followed by a roll on the chart

itself. It is trivial, but it is quite different from modern random charts,

which usually go for weighted results for every level. The matrix mixes up the

results by occasionally introducing lower-level (more powerful) monster types

to the first dungeon levels, or hordes of low-level types for the depths below.

Dangerous monsters travel up from the depths, and weaker creatures band

together to establish strongholds and outposts in the deeper reaches. Consider

the following expedition, going down to Level 3 and back, with two encounters

on the average each level (it is not stated, but usually implied that the

number of creatures appearing will be worth one dice per baseline, adjusted

upwards and downwards):

- LVL 1: 6 Kobolds (LVL 1)

- LVL 1: 3 Lizards (LVL 2)

- LVL 2: 1 Hero (LVL 3, a 4th level Fighting Man)

- LVL 2: 1 Manticore (LVL 5 – ooops!)

- LVL 3: 2 Superheroes (LVL 5, 8th level Fighting Men)

- LVL 3: 9 Gnolls (LVL 2)

- LVL 2: 2 Ogres (LVL 4)

- LVL 2: 3 Thaumaturgists (LVL 3, 5th level Magic-Users)

- LVL 1: 2 Goblins (LVL 1)

- LVL 1: 1 Swashbuckler (LVL 3, 5th level Fighting Man)

Although

basically meant for on-the-run wandering monsters, this little chart comes into

its own during stocking dungeons. Follow the general stocking procedure for

rooms along with the room treasure charts on p. 7, and you will soon have

something fairly serviceable for a starting effort. It is quick and a lot of

fun. Of course, for established monster lairs, I would use a higher “No.

Appearing” – perhaps not the 40-400 goblins of the outdoor charts, but at least

1d8*5 for a start – if it’s got treasure, it can defend it. You can also expand

the monster listings, or “slot in” alternate subtables while preserving the

master matrix. You could have one for mediaeval fantasy, desert tomb-raiding, undercities,

or what have you.

|

| The AD&D Matrix |

Now, I am not 100% happy with this table – chalk it up to personal preference, or the benefit of hindsight. I do believe it goes too deep. Six levels of difficulty should be enough, for a neat 6×6 matrix. Second, it is weighted towards the more powerful encounters, dredging up deep horrors as soon as you enter Level 3. On Level 2, you are more likely to encounter Level 3 monsters (Wights, 4th and 5th level NPCs and Giant Snakes) than Level 2-ones; on Level 3, you will regularly meet Mummies, Wyverns, Hydrae and Balrogs. On the other hand, fun low-strength critters are phased out too soon – Orc, Skeletons, Bandits and the like disappear after Level 2. That is too steep for a good difficulty curve. In our LBB-only, reasonable by-the-book Morthimion campaign, I have adjusted things by using the Level 1 charts for the first two levels, Level 2 for the second two, and so on: that was more than enough for a modern OD&D game (i.e. one played casually, not obsessively every day, every week, as people would do in the 1970s). I also tended to bump treasure values up by one row for largely the same reasons.

|

| E..excuse me, is this Level Two? I thought this was Level Two |

All that said, the OD&D monster table is an excellent example of compact, elegant design. With a few alterations – cut it down to 6 levels, rebalance a little, increase encounter numbers for some monsters – it would be powerful even in our day and time. I would adjust it just slightly, but keep the “dipper” aspect. AD&D’s equivalent dungeon encounter chart (Appendix C) is certainly more balanced, but missing some of the cool chaos introduced by its predecessor. It is weighted a bit too much towards “slog” instead of “swing”. Somewhere between the two, I believe we could find the perfect monster encounter chart.

The cut-up method by William Burroughs comes to mind (cutting up and rearranging words on a page to gain new meanings), or maybe even Une semaine de bonté, Max Ernst's "surrealist" graphic novel that consists entirely of re-appropriated dime novel illustrations. It is noted by Burroughs, though, that you may control what goes in by selecting the page or the words, you cannot get much more than invested unless you have the ability or luck to interpret a random jumble of words. This is where plain monster encounter tables from the 1st (or 2nd) ed. AD&D start to suffer. The majority of wilderness encounters will be with dumb monsters (unless you start to add bells and whistles of your own, at which point they require pre-work and cease to be random encounters) with options to whack the critters or flee from them, with not much in between. I suspect this contributed to their disuse and fall from actual gameplay.

ReplyDeleteJust as I look to my left, I can see Une Semaine de Bonté peering back at me from a bookshelf. Sinister! (I also own two books from the filthy old pervert, but they are obviously on a back shelf, out of sight of innocent eyes.)

DeleteI disagree on the creative content of random monsters: the context of each encounter, a interesting circumstance (even a reaction roll) or random whimsy can easily turn them memorable (consider the giant ants, the suspicious woodsmen around the fire, or the forest women from Monday's game). Not always, of course.

(Teenage Munchkin sounds like a college rock band. Btw did you know that Kyuss, the stoner group got its name after the Greyhawk monster?)

DeleteRegarding WB, once you move past the gay-alien orgies (they are appalling for a reason - as the author puts it, the description of the illness is necessarily obscene) and the junkie misery, the word-sludge passages on twisted ages or space conspiracies show an uncanny resemblance to the output of hipster fantasy content generators, or even hints from the ToAD table above. For example, "the reservoirs are empty, brass statues crash through the hungry squares and alleys of the gaping city" or "in the limestone cave met a man with Medusa's head in a hat box and said be careful to the customs inspector". Pretty evocative I think.

Burroughs does have some useful content. The invocation say the beginning of Cities of the Red Night is the epitome of Gygaxian Chaos: nihilism, immorality, cruelty, sickness, and the veneration of freakish monster gods!

Deletehttps://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/313870340/original/7a08342d2e/1612529782?v=1

There's probably more interesting and inspirational material in that book, but I recall quitting after a few chapters last time for good reason.

An interesting note re: origin of all the random tables in the back of the 1E Dungeon Master's Guide:

ReplyDeleteSome or all of them are probably from Judges Guild.

Bob (the Original Bob) once told me that when Gary was working on the DMG, he sent Judges Guild a preliminary copy of his work. Bob looked it over and though it lacked something -- random tables. So he packed up a bunch of random tables they had sitting around and sent them on to TSR.

Now how much of that they used, if any, I cannot be certain; I never got to ask Gary how that went.

I am pretty sure the encounter tables and magic item are all Gary's; that's his style, and they are core to the game. But the rest of them -- from Appendix F on, and various other tables sprinkled here and there in the DMG -- those look like they are straight out of an issue of the Judges Guild Journal.

Note too how Bob and Judges Guild got a special acknowledgement on page 8.

Perhaps Tim Kask or Mike Carr know? I think they'd be the only ones alive who helped Gary on significant portions of the DMG.

Even though we can no longer ask Gary and Bob about the precise extent of their collaboration, Bob basically told me the same in a now ancient 2002 interview for Chaos Ultra, a Hungarian fanzine (originally a diskmag!). Here is what he said on this matter:

Delete"Q: Gary Gygax credited you in the AD&D rulebooks and even recommended your supplements. Are there rules and elements that could be considered your children? And, overall, how did AD&D change the game? Was it for the better or the worse?

A: Gary sent me the prepublication manuscript and I sent him back hundreds of pages of campaign rules and encounter tables I used. Despite their contract never to produce their adventures themselves and treat our license as an exclusive, TSR did their own. Despite the contract to advertise every Judges Guild product within the pages of every product, TSR did not obey their own contract."

The full interview is still preserved here: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/necromancergames/interview-with-bob-bledsaw-t7450.html

I'm surprised one of Yoon-Suin's tables didn't make the cut. Too setting specific?

ReplyDeleteI consider Yoon-Suin one of the great achievements in old-school gaming - alongside the ToAD, Anomalous Subsurface Environment, and the Wormskin fanzines - but there was no specific table in there that has become a mainstay in my games. In Yoon-Suin's case, it is more about the whole work - marrying an exotic fantasy setting to properly run old-school D&D - than a specific part of it.

DeleteThis is the heart of (A)D&D to me - not the modules. It's finding out what lies between here and there; first the DM, in preparing that after finding out where the group's goal is, and then the players in play. Perhaps that changes the original goal; perhaps it's merely challenge that makes reaching the original goal an accomplishment.

ReplyDeleteBut much was lost when DMs specialized in running modules, because for the most part modules aren't (and can't be) overly interested in what lies between them and a point that could be anywhere. That's left to the DM who's no longer very practiced at making and running that type of content.

This would be the true message and purpose of the DMG - its role as a reference work (although a very messy one) transcended by its role in opening the reader's eye to the Big Picture of a fully developed, complex campaign of interlocking small parts. What those parts are, and how each one operates, is welcome detail but coincidental. The DMG gives you the vision. AD&D's critics, including not a few B/X players, miss this point. But that is perhaps the subject of another post... about Greater D&D!

DeleteHow modules fit in there can be slavish, and I understand your caution about getting trapped in them. Properly integrated, with context, ties, and above all continuity, they can find their proper place, and I think they are indispensable in transmitting inspiration and good play. There is also much about campaigns which is elusive, a product of the moment. Hard to recount and impossible to bottle, but present at the table.

I agree, modules are indispensable for reasons of convenience if nothing else. Modules are to campaigns what set piece rooms are to dungeons - you have to have them, whether home made or purchased.

DeleteAnd like a dungeon where set pieces are appreciated both for what they are, and also for the sense of accomplishment in finding them, a good location serves the same purpose. The trick is making the finding enjoyable without dispensing with it.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteGreat Post! As some might know, a bunch of other DM's and myself are running a shared campaign using the DMG as our foundational & procedural text. The resulting millieu is not only exciting but it is very gameable and has a rather peculiar scope. As such, being a heavy user of the random wilderness, random fortress and random encounter tables and using JG-products as adjuncts I must say: the DMG tables are much more refined. They mesh better, as if they were edited by somebody with a lot of D&D experience. They are much more polished and smooth in their interaction than any comparable JG product. I wonder who added this refinement. Part of me wants it to be Gary, but if not Gary who, and why are the proper JG-tables and subsystems so much rougher around the edges?

ReplyDeleteWell, that was Gygax's pretty consistent (and contoversial) MO - taking raw materials from other folks (core Chainmail by Jeff Perren (and maybe Leonard Patt), core D&D from Dave Arneson, core thief class from Gary Switzer, core planes cosmology from Steve Marsh, core S1 from Alan Lucion, core S3 and S4 from Rob Kuntz) and editing and revising them to fit his gamer sensibility, and in all cases pretty inarguably making them better and more useful and game-able. However, in so doing he tended to credit himself as primary (or sole) author, which of course rubbed those other contributors (and latter day fans who've decided to champion them) the wrong way. Given all that, it's absolutely credible that Bob Bledsaw sent Gary a whole bunch of tables for inclusion in the AD&D DMG and that Gary revised and edited them and then claimed those revised/edited versions as his work and that a "thanks to" credit was sufficient acknowledgment of the original contribution. Which seems kind of shitty looking back, but hey, the alternative in pretty much all of these cases is that the stuff would've remained unpublished and unknown - it's not like anyone else was offering to pay these guys either.

DeleteAt this point, it is water under the bridge - in the answer he gave me in this interview, Bob did not seem upset about it - while he *did* bring up TSR's failure to abide by their publishing agreement. (JG being the Paizo of the day, they were a serious business with probably as many employees as early TSR.) AD&D's development still took place in the hobbyist phase where everyone wins by sharing, and there is no market share to fight for, just vast new territories to conquer. Not quite the same situation as years later, or especially today's shrinking vestige of an industry!

DeleteIn the end, you are right too - whatever their exact provenance, these appendices continue to be a vast mine of inspiration and useful material. I think both gentlemen deserve a raised glass of Lacrima Güntheri.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteSpeaking of the Wilderlands, some maniac compiled a lot of the JG hex generation stuff into a big document called 'the wilderness hexploration guidelines.' It includes the Ruins & Relics tables, but also material for generating castles, temples & shrines, lurid lairs, etc.

ReplyDeletehttps://drive.google.com/file/d/1kjlkqfqWTQoHOr5FIvw4uT3lmaW7bsiH/view?usp=sharing

That's an excellent resource - like Kellri's netbooks, an accessible and modern compilation of a lot of good stuff. Highly recommended!

DeleteHey man, just wanted to say I recently discovered your blog and am having a great time reading through it. I ran Xyntillan with my group using Knave for our first quarantine campaign and a great time was had by all.

ReplyDeleteI was quite curious as to the status of the Helvéczia RPG. I have a weirdly persistent interest in running some kind of 17th century romp through Europe (despite knowing next to nothing about it apart from some Solomon Kane stories), and your game sounds pretty great. Any idea how long we’ll be waiting until we get our grubby hands on it?

Great to hear you are enjoying the module!

DeleteWRT Helvéczia, the news I can give you is *very* recent: I closed the manuscript on the 24th of March, and handed it to my printer. The first regional supplement / adventure collection will be finished tonight (I have to translate a single page and it is done), and submitted for printing after Easter. Binding for the hardcover rulebook, and manufacturing for the boxed set will take some time (the boxes are handmade, very sturdy stuff), so late April looks realistic.

This is more a "history-light" game than one which takes thorough study to even play; if you enjoy swashbuckling films, the Brothers Grimm, the Three Musketeers or indeed Solomon Kane, that's a fine grounding. If you have read Vance's Cugel stories or Leiber's Ffahrd / Grey Mouser tales, you already know picaresque adventures.

The book offers a basic picture of the time and place, and it has an Appendix N style list of inspirational sources you can get into if you have the time and/or inclination. I can wholeheartedly recommend LeSage's Gil Blas to anyone: it is as fresh today as it was in 1714, and has as much plot in its first thirty pages as the average modern fantasy novel. Here is a recent translation with a free preview of the first chapters: https://www.amazon.com/History-Gil-Blas-Santillana-translated-ebook/dp/B008C29V62

I will make an announcement reasonably shortly, too.

Thanks mate, looking forward to it.

Delete