|

| ...very pleased to meet you |

The random element in D&D gameplay is one of the great, underappreciated design features of role-playing games. We rarely question its presence, and only notice it when it is absent from a particularly contrarian ruleset. Things could have gone differently: if RPGs had emerged from experimental theatre, randomness would presumably play a much lesser, even marginal role. But random chance in game, character generation, and game prep, is at the heart of the role-playing experience, responsible for a lot of its variety and unpredictability. “Roll a saving throw against poison” is one of the tense moments in any adventure – for a moment, the whole world stops as the fate of adventurers hangs in the balance, and great things are decided by the roll of a 20-sider.

Random

and semi-random methods have added a curious layer of chance to running the

game as well. The GM runs the game, but even with a pre-written adventure, he

does not know exactly what game he will be running. What if the players

blow a few crucial rolls and they cannot get through a particular locked door?

What if the bad guys roll terribly, and a dangerous foe goes down in a few

rounds of desperate melee? What if a random encounter is taken as a major clue,

derailing the course of the campaign? These factors, even beyond player

decisions, make sure we are kept guessing – and hopefully at the edge of the

seat.

And

of course, random generation is useful in preparing adventures, from the

general framework to the room- or encounter-level descriptions. Random tables –

used intelligently – take our mind where it would not go without prodding. What

the computer people call “procedural generation” can determine a lot of incidental

detail in a lot of CRPGs beyond the basic RNG – going all the way to the construction

of random landscapes and political systems. But computers have not been given

an imagination yet: they work fast, but they can only regurgitate and combine;

they cannot truly create and interpret. And so, tabletop gaming’s random tables

remain wedded to a combination of random rolls and the human personality. Your

take on “ruined tower, giant snails, archives” will be different from mine, and

from one random “seed”, we would build radically different worlds.

Of

course, not all tables are created equal. We may try a lot, but we will

gravitate to a few which are particularly useful.Some are plain better, more

useful than others. This is why I present here my personal list of favourites, all

of which I have used extensively due to their usefulness and longevity. No distinction

is made here on the basis of age, nor official or unofficial status: tables

are a meritocracy. However, there is no order to the choices in this final

selection: all are great in their own way, and to rank them further would not

be useful. So!

*

* *

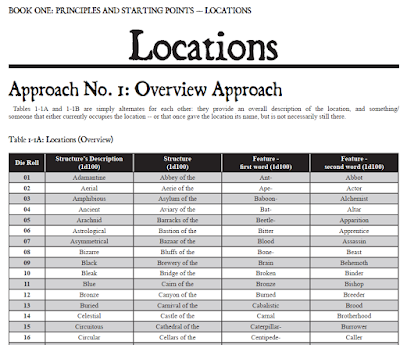

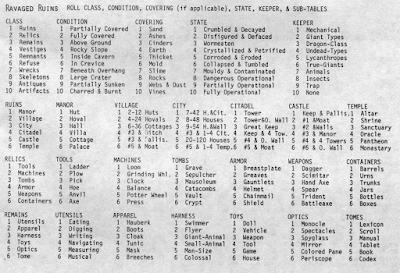

The

Concept Generator: The Locations (Overview) Table (Tome of Adventure Design)

It

would take long to sing the praises of the great ToAD, this modern classic of utility

products, so let it suffice that its over 300 pages of tables is an

inexhaustible mine of what the author, Matt Finch calls “deep creativity” –

half-formed idea fragments which emerge into full-blown game material. Like

Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu, its treasures are endless. Someone in the middle,

there is a four-page 1d100 table for the generation of random thrones. There is

enough in that table alone to create and stock The Dungeon of Thrones, if you

wanted to. That’s the kind of book the ToAD is. But there, among the tables for

“complex architectural tricks”, “corpse malformations”, “religious processions

and ceremonies”, and “mist creatures” – which I am sometimes using – there are

some that come up all the time (such as a table collection for generating

individual-, item-, location-, and event-based missions), and one that

is beyond useful. And this is actually the first table in the book: the

“Locations (Overview)” table.

|

| The Locations Overview Table |

This is a four-column 1d100 table to create basic concepts for major locations (there is one for dungeon complexes, dungeon rooms, and strange features, of course – the book scales down nicely). It could work as a module title generator, of the “Adjective Noun of the Adjective Noun” variety. I have been using this particular table since its original appearance in Mythmere's Adventure Design Deskbook, vol. 1., and found it a great companion for coming up with the initial building block of future adventures, or just interesting places to scatter in a campaign world. Consider these examples:

- Moaning

Chapterhouse of the Bat-Sorcerer

- Collapsing

Edifice of the Many-Legged Burrower

- Dilapidated

Castle of the Bitter Apparition

- Aerial

Cliffs of the Hyena-Keeper

I

am not saying every one of these results does something for me right now, but

three or four rolls almost always provide a basic framework to build on. I can

imagine the Moaning Chapterhouse of the Bat-Sorcerer as a place in a campaign

inspired by Clark Ashton Smith’s Hyperborea stories, and the Dilapidated Castle

as a locale in a chivalric high fantasy/fairy tale setting. The other two, as

the average result tends to be, is weird fantasy; the Aerial Cliffs are

great, while the Collapsing Edifice just gives me “centipede monster lair”, and

that’s not much added value. The other three, I could use. Sometimes, I take a

folded paper sheet, and fill one page with random idea seeds that seem to fit

my current mood, then build an adventure around them (The Singing Caverns

from Echoes #01 was partially built with this method).

Of

course, there is something about this table I have not noted yet: it is not

just one table. It is followed by another identical d100 table with different

keywords (Sinister Grotto of the Howling Wolves… OK, this is not much – but how

about Fossilised Pagoda of the Mist-Pirates, the greatest wuxia OSR adventure

never written?), and a two-column table that uses the “purpose approach” for

truly weird but sometimes quite cool results (Skin Altar, Time-Well, Spider

Separator [?], Perfume Pools [that’s a winner]). That’s a lot of stuff to work

with. You could fill a mini-setting with adventures based solely on these

tables, because why not.

*

* *

|

| Muddle's Generator |

The

Wilderness Workhorse: Muddle’s Wilderness Location Generator

Yes,

this is an

internet tool, and you can try it for free, so go

ahead. The ToAD, exhausting as it is, is not much focused on wilderness play,

and its tables in this section are cool but just not as varied as the dungeon

chapter. Muddle’s wilderness table is a good alternative. It combines nouns and

adjectives into a list of 50 locations for your wilderness adventure. A lot of

these results will be irrelevant to your current project, but you can check

these and delete them, then replace them with a new batch of entries, repeat

until you have the precise 50-entry roster you need. Here are the first few

from the selection I got this time:

- Deep

Hills of the Elder Piller (sic)

- Mausoleum

of Adamantite Drows

- Dreary

Treasury

- Inner

Tomb

- Skeletonelder

Hole

- Slimefist

Tower

A

lot need to be weeded out (I have developed a soft spot for Awful Peak, it is

staying), and the vocabulary is much more limited than Mythmere’s thesaury

(Sorry! Sorry!), but it is quick, cheap, and often does its job. You can use it

to build. Deep Hills of the Elder Pillar sounds like the place where people

possess a lot of good ol’ folksy wisdom, much of it involving goat sacrifice

and non-euclidean things, Dreary Treasury is a place offering an interesting

internal contradiction, and Inner Tomb either lies deeper in the wilderness, or

it is a tomb with a hidden sub-section. And we have a cultist hideout at the

end, I believe.

But

that’s not all! Muddle’s set also has a dungeon room generator that’s almost as

decent, and you can force it to select

by theme. The other tools are less useful, although the deity generator might

make Petty Gods a run for its money (Grundermir Ratvoid, Dread Fiend of

Bad Breath; Malumdrim Biscuitfinger, Queen of Ants; Asheeltrym Grumblespoons,

Lord of Bannanas (sic); Mulelroun, Godess of Apples; and Grelderthul the

Beautiful, Queen of Aggression is certainly a pantheon).

*

* *

The

Implied Setting: Outdoor Random Monster Encounter Tables (AD&D Dungeon

Masters Guide)

In

the book that has everything, everyone will find something. Gary’s magnum opus

is less methodical guidebook than an occult tome that teaches you, the

fledgling DUNGEON MASTER, that horizons are infinite, and the true scope of the

reaches far beyond a few narrow possibilities. Last evening, we looked up its

advice on underwater combat after two characters fell into a deep pool inhabited

by a water spider, and I am sure the “how much damage will I take in my armour

type if I transform into a specific lycanthrope type” table has been useful to

someone, somewhere – at least once in history.

When

the DMG’s readers are asked which is the most important section in there, the

teenage munchkin will say “Of course it is the magic items table! Here, have

a vorpal mace and two Wands of Orcus!”. The journeyman will point to

the dungeon dressing appendix – it is useful indeed – and the old-schooler will

at once point to Appendix N for its listing of AD&D’s thematic roots, which

we all know is better than the stupid dreck everyone else is reading. The connoisseur

of obscure gems will note the “Abbreviated Monster Manual” from Appendix E. Bad

people who need to be put on a watchlist will cite “the Zowie Slot Variant”. These

are not bad answers, but for my pick, I would go with Appendix C, AD&D’s

outdoor encounter system.

|

| You encounter 2d6 Catoblepas |

Random

dungeon dressing and treasure tables help you fill your rooms, and Appendix N

will help you develop a refined taste in genre literature; Appendix C gives you

the most practical tool for AD&D’s implied frontier setting. We can

appreciate the points of light concept because it gives us our points of

light in the practical sense – not as aesthetic, but also as practical procedure.

Random encounters, particularly when also used to populate

wilderness areas, as in a hex-crawl, give you the gameplay texture to make

expeditions in the outdoors varied, fun, and very hazardous. That is, they give

you the everyday reality of travelling between two points on the landscape. Here

is an expedition of six encounters moving between two cities separated by

plains, then hills, a stretch of forest, more hills, marsh, then plains again,

assuming one encounter occurring on each stretch:

- Plains:

Men, nomads (150), with 13 levelled Fighters between 3rd and

6th level, a 8th level Fighter leader with a 6th

level subcommander, 12 guards of 2nd level, plus two lesser Clerics

and a lesser Magic-User. Assuming the nomads do not force you back in town, or

just take you as captives, we can move on to…

- Hills:

Elves (140), with 10 levelled Fighters of 2nd or 3rd

level, 3 Magic-Users of 1st or 2nd level, and 4

multi-classed elves (4/5 level, plus a 4/8 leader). Let us not consider the

giant eagles in their lair – the elves are bros, anyway. We share lembas and

move on.

- Forest:

2 Giant weasels, which are 3 HD creatures. Luck was with us, unless the

encounter occurs by surprise, since giant weasels suck blood at a rate of 2d6

Hp/round. They have no treasure, but their pelts are worth 1d6*1000 gp, each enough

to hire 100 porters for 10 to 60 months of work, or an army of 50 heavy footmen

for the same time span!

- Hills

again: 16 Wolves, the basic unit of fantasy wildlife. They are 75% to be

hungry when you meet them. Of course, they are hungry this time, too.

- Marsh:

this is a great place to meet a beholder, catoblepas, or other high-level

monsters, but instead, we get Men, pilgrims (60), 9 Clerics of 2nd

to 6th level, and a 8th level Cleric with a 3rd

to 5th level assistant. There is 60% of 1d10 Fighters (random level,

1st to 8th), and 30% for a Magic-User of 6th

to 9th level, but they are not here right now. Still, these badasses

are travelling in the world’s most dangerous terrain type except mountains.

Don’t screw with.

- Plains

again: 1 Huge spider, which is a good roll on 1d12, and fortunately, it is

not the calf-sized 4+4 HD type, but the dog-sized 2+2 HD type. The only

downside is that they surprise 5:6, which is a bad value, considering

their poison is deadly.

|

| Just a random encounter, bro! |

After

this trip, you start to appreciate those sexy harlot encounters in the city (and

hope if it comes to worse, it is 8th to 11th level

Thieves out for your purse, and not a Weretiger or a Goodwife out for your

blood), and you start understanding why those points of light remain points,

not larger blots, or why those pilgrims travel in groups of 10-100. It also

puts your mind into a different frame than level-balanced games with random

monsters numbering in the 1d4 or 1d8 range. You can’t fight all those roving

death armies, and besides, it does not pay (weasel pelts excepting). You learn

to scout, you learn to run, you learn to leave behind food to distract your

pursuers (this scales up from rations to pack animals and fellow adventurers –

as the great Grey Fox once shouted back to a companion stuck in a bad situation,

“What ‘party’? The party is already over here!”), bribes of gold or good,

old-fashioned bullshitting to tip over that reaction roll. You learn to grovel

before that dragon, planning future revenge. You learn to plan an ambush to

plunder that lair you just discovered, and carry away the best valuables. Welcome

to the AD&D World Milieu!

*

* *

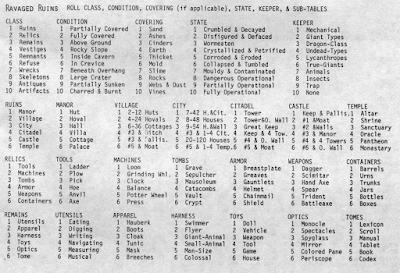

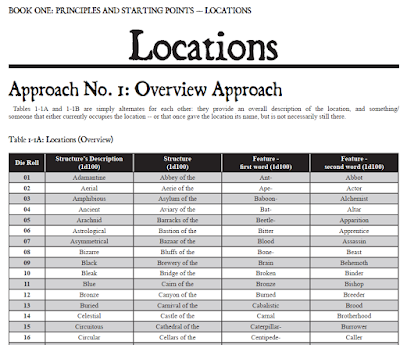

The

Chad Sword & Sorcery Milieu: Ravaged Ruins (Wilderlands of High Fantasy /

Ready Ref Sheets)

|

| Wilderlands of Highly Awesome |

So

you got to know Appendix C, and suddenly gained a new understanding of

AD&D. You are on a different level. Here is where it gets stranger. From

the OD&D era, Judges Guild’s Wilderlands setting presents a truly bottom-up

sandbox setting of minimal detail and high weirdness – recognisably D&D

fantasy, but more “Appendix N” and Frazetta than the comparative classicism of Greyhawk

or Steading of the Hill Giant Chief. The “High” in Wilderlands of High

Fantasy might stand for something else than “Tolkienesque” here, even

though the setting also has a generous helping of Tolkien pastiche – right next

to old-school Star Trek, classical mythology, pulp fantasy, and Dark Ages

Europe/Near East mini-kingdoms. It is just general fantasy enough to kick you

out of your comfort zone when it turns out the Invincible Overlord has captured

a stray MIG fighter, or that the dungeons under Thunderhold, castle of the

Dwarf King have half-buried railway tracks and a gateway to Venus on their

fourth level. The described Wilderlands is filled with odd, short idea

fragments and juxtapositions, a few throwaway lines like

- “Villagers

charged with a centuries old oath to the ‘King of the Lost-Lands’, maintain an

eternal bonfire atop a crag to warn ships off the hidden reef.”

- “In

a well hidden crypt is a ring of Brathecol, one of the kings of old Altantis.

(sic – ‘Altanis’ vs. ‘Atlantis’ is one

of the strange ambiguities of the setting)) A stone golem is guardian of the crypt which appears as a

monolithic block of limestone.”

- “The

crystallized skeleton of a dragon turtle is buried on the sandy beach. The

skull houses a giant leech.”

However,

there is also a procedural Wilderlands that lives in its weirdo random

tables and guidelines, which were collected in the supremely fun Ready Ref

Sheets, Volume I (no second volume was released, but the first one is a

great look into OD&D, and remarkably easy to obtain). Here you can find

rudimentary rules for taxation, trade and mining – but the most useful table is

the self-explanatory Ravaged Ruins. This table generates wilderness locations

to scatter across your hex maps, and let your players wonder about the fallen

glories of past ages – something that already establishes one of the major

themes of the Wilderlands. The table is relatively small, a simple two-pager

with results drawn from archaeology... at least at first glance. It generates a

basic ruin type, with nested sub-tables to determine the specific subtype –

there are not that many results, but the number of combinations is at least

decent. Supplemental columns also establish the condition of the ruins, their

covering (definitely archaeological in sensibilities), state, and the monsters

guarding the ruin. And it gets weird, as seen in these six rolls:

- Statued

fountain, found in a large crater, covered with vines, crumbled and decayed,

protected by lycanthropes.

- Bones,

above ground and covered with slime, partially operational, no guardians. (What

does partially operational mean in the case of a bone pile? Mediocre Judges

will frown and reroll. Superior Judges will find an explanation. Perhaps this

is a bone mine of extinct creatures, still excavated by locals as trade goods

or building material? What of the slimes?)

- Sea-horse

carriage, partially sunken and buried in a thicket, dangerous operational,

protected by insects.

- Periscope

inside cavern, covered in rocks, collapsed and tumbled, mechanical guardians.

(Wait a minute! We are not in Middle Earth anymore, Bilbo!)

- Man

o’ War inside cavern, dangerous operational, protected by trap. (It has to be a

fairly big cavern for that… and what if we roll it for a place far, far from a

sea coast?)

- Asphault

(sic) road, partially covered in thickets, corroded & eroded, protected by

giant types. (So this setting has old, overgrown, eroded asphalt roads.)

|

| Ravaged Ruins |

Something, even a random detail, becomes a theme through repetition and exploration: and this is the Wilderlands’: picking through the remnants of older ages, part Dark Ages, part Classical Antiquity, part fallen star-faring civilisation. Antigrav sleds, nuclear submarines and re-entry capsules lie wrecked in ancient ruins guarded by dragons and mechanical guardians next to crystallised skeletons and eroded old idols; the grand works of past cultures lie abandoned in dusty deserts and frozen tundra. There are rat chariots pyramidal palaces. What is this place? In a compact, two-page table, Wilderlands of High Fantasy speaks louder, and in a more game-relevant way, than a full supplement. Yes, this table can be exhausted through use, but by that time, you get the Wilderlands.

*

* *

The

Panic Button: The Table of Despair (Original D&D Discussion / Fight On!)

Not

every great table is enormous, and this one is just a throwaway

forum post by korgoth. However, The Table of Despair is a great gameplay

innovation, and a high achievement of old-school design. It becomes useful when

the characters don’t get the hell out of Dodge before the curtain falls; when

someone is separated from the main party for longer than healthy, or when

someone flees in blind panic. You roll on the table and weep, mortal. Those are

not great odds – in fact, they are downright crummy odds – but this is Jakkalá,

and they may in fact be the best odds you can get. All that for a fistful of

káitars!

|

| The Table of Dessssspair! |

Aside

from its chuckling evil glee, the table communicates the danger of the Underworld

very clearly. The results are appropriate, and should be pronounced in a

booming, hollow voice. It is not applicable to every campaign, and it is a bit

repetitive, but it is a work of simple genius. I have included a milder variant

in Castle Xyntillan (“The Table of Terror”), which is derived from Helvéczia’s “Through

Branch and Bush”, but all of these trace their lineage back to korgoth’s now

classic post.

*

* *

|

| The Carousing Table |

The

Equation Changer: Party Like it’s 999 (Jeff’s Gameblog)

Curiously,

very little of the definitive old-school gaming blog has seen print; Jeff

Rients just wrote tons of material he gave away for free. And 2008 was a great

year, even by the Gameblog’s standards. These carousing guidelines

are not radically new, since they build on older principles which go right back

to Orgies, Inc. (The Dragon, 1977) and even Dave Arneson’s First

Fantasy Campaign (Judges Guild, 1977), already in vogue by 2006-2007. But

Jeff’s take is the iconic, recognised version; he was not there the earliest,

but he was there the mostest. It is simple: at the start of every session, you

can just throw away a bunch of gold pieces in wild parties, and earn the same

amount in experience points. There is, also, a random table to add risk and

complication to the downtime activity. The party may have just been looking for

some good fun and easy XP, but a few bad rolls later...

- Brother

Otto wakes up with the hangover from hell, cramping his spellcasting.

- Nick

the Knife accidentally burned down the inn, and everyone in town knows.

- Sir

Wullam wakes up and finds himself with the symbol of the Brotherhood of the

Purple Tentacle tattooed on his... oh no! Oh nooooooo!

- Sorceric

has a minor misunderstanding with the guards, and is hauled in for six days in

the lockup.

The

adventure has not even started yet... or has it just started?

|

| At least this inn is not on fire, RIGHT, Nick? |

The

carousing rule inverts D&D’s core equation, the 1 gp = 1 XP rule. Here, you

do not gain XP for treasure you find, you gain XP for treasure you spend. AD&D’s

model – which, mind you, works great, although for different reasons – hoovers

up excess gold from the campaign through training costs (most of my current Hoard

of Delusion party is stuck at their current level, having the XP but not

the gp for training), and introduces the strategic dilemma – do we spend it on

advancement or other useful stuff? It is also quintessentially 80s action movie

– our hero, experiencing hardship, goes to the gym or the old karate master to

bulk up for the tougher challenges coming his way. The inverted model removes

money through living it up through excessive partying. OD&D’s upkeep rule

is a predecessor (1% of your current XP total per arbitrary time period), but

Jeff’s carousing table turns it into a mini-game and a source of new

mini-adventures. You can also see Ffahrd, the Grey Mouser or Conan doing this,

more than them learning new moves under the watch of a wise old instructor. Of

course, it is just a table of 20 entries, with a comical aesthetic. But it is a

hell of a beginning. I have my own 64-result downtime complications table from

the Helvéczia RPG: here are four results for late 17th century

picaresque adventures:

- One

of Father Gérome Gantin’s noted enemies has vanished from town, and everyone is

eyeing him suspiciously.

- Bettina

von Vilingen, the noted scoundrel, finds herself the elected mayor of a tiny podunk

village.

- Sebastiano

Gianini, Bettina’s partner in crime, has indulged in sins better left unmentioned,

and loses 3 Virtue.

- Domenico

Pessi, retired mercenary, survives a close encounter with Death, but to correct

the mistake, the Grim Reaper is once more on Domenico’s trail...

*

* *

The

Dipper: The Monster Determination and Level of Monster Matrix (OD&D vol. 3)

For

our final table, let us return to the roots: OD&D’s random monster chart. OD&D

has often been called badly designed (and until its mid-2000s revival, it was

mostly considered a historical footnote), but what it is is badly written,

and barely if at all explained. The design itself, taken at face value instead

of handwaved or second-guessed, is surprisingly tight – blow the dust off of

the covers, and you find yourself something that hangs together quite well as a

game. We have already mentioned AD&D’s wilderness encounter charts – here is

a simple, elegant and universal matrix for running expeditions into the

Mythic Underworld.

|

| The Dipper |

The

matrix cross-references level depth – the basic measure of zone difficulty –

with a 1d6 roll to select a random chart, followed by a roll on the chart

itself. It is trivial, but it is quite different from modern random charts,

which usually go for weighted results for every level. The matrix mixes up the

results by occasionally introducing lower-level (more powerful) monster types

to the first dungeon levels, or hordes of low-level types for the depths below.

Dangerous monsters travel up from the depths, and weaker creatures band

together to establish strongholds and outposts in the deeper reaches. Consider

the following expedition, going down to Level 3 and back, with two encounters

on the average each level (it is not stated, but usually implied that the

number of creatures appearing will be worth one dice per baseline, adjusted

upwards and downwards):

- LVL

1: 6 Kobolds (LVL 1)

- LVL

1: 3 Lizards (LVL 2)

- LVL

2: 1 Hero (LVL 3, a 4th level Fighting Man)

- LVL

2: 1 Manticore (LVL 5 – ooops!)

- LVL

3: 2 Superheroes (LVL 5, 8th level Fighting Men)

- LVL

3: 9 Gnolls (LVL 2)

- LVL

2: 2 Ogres (LVL 4)

- LVL

2: 3 Thaumaturgists (LVL 3, 5th level Magic-Users)

- LVL

1: 2 Goblins (LVL 1)

- LVL

1: 1 Swashbuckler (LVL 3, 5th level Fighting Man)

Although

basically meant for on-the-run wandering monsters, this little chart comes into

its own during stocking dungeons. Follow the general stocking procedure for

rooms along with the room treasure charts on p. 7, and you will soon have

something fairly serviceable for a starting effort. It is quick and a lot of

fun. Of course, for established monster lairs, I would use a higher “No.

Appearing” – perhaps not the 40-400 goblins of the outdoor charts, but at least

1d8*5 for a start – if it’s got treasure, it can defend it. You can also expand

the monster listings, or “slot in” alternate subtables while preserving the

master matrix. You could have one for mediaeval fantasy, desert tomb-raiding, undercities,

or what have you.

|

| The AD&D Matrix |

Now,

I am not 100% happy with this table – chalk it up to personal preference, or

the benefit of hindsight. I do believe it goes too deep. Six levels of

difficulty should be enough, for a neat 6×6 matrix. Second, it is weighted

towards the more powerful encounters, dredging up deep horrors as soon as you

enter Level 3. On Level 2, you are more likely to encounter Level 3 monsters (Wights,

4th and 5th level NPCs and Giant Snakes) than Level

2-ones; on Level 3, you will regularly meet Mummies, Wyverns, Hydrae and Balrogs.

On the other hand, fun low-strength critters are phased out too soon – Orc,

Skeletons, Bandits and the like disappear after Level 2. That is too steep for

a good difficulty curve. In our LBB-only, reasonable by-the-book Morthimion

campaign, I have adjusted things by using the Level 1 charts for the first two

levels, Level 2 for the second two, and so on: that was more than enough for a

modern OD&D game (i.e. one played casually, not obsessively every day,

every week, as people would do in the 1970s). I also tended to bump treasure

values up by one row for largely the same reasons.

|

| E..excuse me, is this Level Two? I thought this was Level Two |

All

that said, the OD&D monster table is an excellent example of compact,

elegant design. With a few alterations – cut it down to 6 levels, rebalance a

little, increase encounter numbers for some monsters – it would be powerful

even in our day and time. I would adjust it just slightly, but keep the “dipper”

aspect. AD&D’s equivalent dungeon encounter chart (Appendix C) is

certainly more balanced, but missing some of the cool chaos introduced by its

predecessor. It is weighted a bit too much towards “slog” instead of “swing”.

Somewhere between the two, I believe we could find the perfect monster

encounter chart.