|

| The Hall of Mirrors shifts... |

This blog started on 5 August 2016,

making early August the time of the year to engage in stock-taking and

irresponsible conjecture. Adjusted for inflation, this means early October.

This will be a slightly laconic report: most of the things I have to say are fairly

close to last year, and I don’t wish to repeat myself too much.

The State of the Blog

This year, Beyond Fomalhaut’s activity

amounted to 28 posts, which seems to be the constant (the last two had 29). 18

of these were reviews, and that’s not including the stuff I read but didn’t review.

Pattern recognition has helped a lot in weeding out much of the dreadful stuff,

but from the clunkers that have snuck through, there would have been no joy in eviscerating

most of them. I also failed to review some genuinely good material, including

titles recommended by their authors. For that, I apologise: sometimes, the

stars are just not right, or I didn’t have much that was worth saying.

On the average, the 19 reviews scored at

3.3, slightly above the seven-year total average of 3.11. Some of

this year’s best have come from edited collections. The No Artpunk Contest

has produced a high-quality lineup this year, and I haven’t even finished

reviewing these adventures. One time can be luck, but two times is skill, and

skill can be improved and honed through the spirit of competition and

self-improvement. In the Hall of the Third Blue Wizard was more

of a mixed bag, from really strong stuff to one of this year’s worst efforts, but

I can see it becoming another collection worth watching. Among the other titles,

we can see the continuing trend where the shovelware people have largely moved

on from the core of old-school gaming towards more distant systems, so a lot of

the crap has just disappeared.

Here are the year’s results and special

highlights:

- 5 with the Prestigious Monocled Bird of Excellence.

This rating was not awarded this year. Wormskin, Anomalous Subsurface

Environment, The Tome of Adventure Design, and Yoon-Suin loom

high above the lower peaks, and have not been equalled.

- 5 was awarded to two releases. Vault

of the Mad Baron, by Christian Toft Madsen, took one: a rich, complex sandbox

adventure set in a corrupt city beset by a mysterious plague, combining faction

intrigue with dungeon-crawling in an accessible format. Tomb of the

Twice-Crowned King by Hawk came from the No Artpunk Contest, capturing

high-powered AD&D at its best: from standard building blocks, it constructs

a tomb-robbing adventure with tightly-constructed gameplay and a strong

personality. Among other things, these two modules show that great content and

effective presentation can be reconciled, and the latter lies in practiced skill,

not gimmicks.

- 4 was awarded to seven releases: Wyvern

Songs, a collection of weirdo mini-adventures filled with creative exuberance;

The Crypt of Terror, for

excellence in stickman art living up to

its title with its dirtbag combat challenges and imaginative dungeon tricks; The

Black Pyramid, a temple-delve with active competition; The Cerulean

Valley, a JRPG-style mini-sandbox; Shrine of the Small God, a

dungeon that builds expertly on Meso-American mythology; The Ship of Fate,

which brings Moorcock’s high-level cosmic adventures to your game table; and

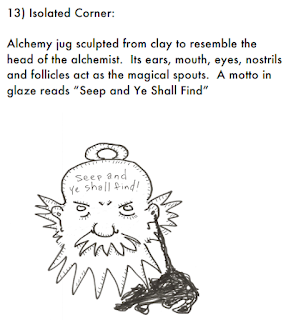

the weird puzzle module Alchymystyk Hoosegow. - 3 was awarded to six products. This

year, five of these have been slightly flawed, but generally strong entries,

with Caves of Respite as a good beginner effort worthy of encouragement.

- 2 was awarded to Expedition to

Darkfell Keep, a shoddily-made dungeon crawl; and DNGN, an

overproduced dungeon-in-a-zine that took common wisdom about presentation and

layout so seriously it ended up killing whatever attraction might have had.

These entries have been conveniently placed in the pillory. Speaking of…

- 1 was awarded to two products, both

outright terrible. In the case of Winter in Bugtown, this is entirely

deserved: the high-concept premise masks a twee Starbucks fantasy setting and a

complete mess of execution which would work decently as a parody of badly done artpunk

– but sadly, it is completely earnest. The recently reviewed Into the Caves

of the Pestilent Abomination is more of an accidental hit on an inept

low-level OSE module (it being OSE is also accidental; top dog systems always attract

this sort) – but I picked it up because it looked interesting, and it turned

out to be a showcase of bad adventure design practices. Unfairly singled out?

Probably. Honoured with one star? Deservedly.

All in all, this was a good year for

well-made adventures, and the variety of styles is good to see. It would be

decent, though, to see the same quality in wilderness and city adventures, or

even good situation-based scenarios. This is underexplored territory, on which

more later.

|

| Sword & Magic Covers by Peter Mullen and Cameron Hawkey |

The State of the Fanzine & Other

Projects

This year, EMDT released eight titles,

with two more to follow next weekend. Some of these are major Hungarian publications:

the Hungarian Helvéczia boxed set with two regional supplements last

December, plus the soon-to-be-published Sword & Magic are the key

titles. This sort of took the wind out of my sails elsewhere, so the zines have

been more modest. I published one issue of Echoes (although a fairly

thick one), the second issue of Mr. Volja’s Weird Fates, and two

modules: The Forest of Gornate and Istvan Boldog-Bernad’s excellent

low-level death-fest, The Well of Frogs. Gornate has received a Czech

edition, and Outremer Ediciones has recently concluded a successful

Kickstarter for the Spanish release of Castillo Xyntillan.

The largest undertaking of 2023 has been

the second edition of Sword & Magic, a slow-burn project finally

reaching fruition. The original edition of the game was published on 15 October

2008 (a few days after the similarly imaginatively titled Swords &

Wizardry), and the release of the new one is planned for 15 October 2023,

exactly 15 years later. Writing and producing two thick hardcovers (168 and 268

pages, respectively) and a 80-page regional supplement is no laughing matter even

if it is a revised edition, a lot of groundwork has already been laid, and I

had the Riders of Doom on my side to give advice, do thorough proofreading, and

help shape the rules from the broadest to the most obscure. It was exhausting,

endless, and it feels really good to see it done. What remains now is to receive

the bound books and start shipping.

|

| Potion of Extra-Barbarism |

This game shall not be translated – there

are enough old-school systems to pick from, and translating, producing and

supporting Sword & Magic in a second language would be beyond my

means. However, that does not mean there will be no dividends for the

English-speaking reader. The second volume is planned to see release as an

OSRIC supplement under the title Gamemaster’s Guidelines Beyond Fomalhaut.

This will be a comprehensive guidebook to creating and running old-school adventures

and campaigns, ranging from basic and advanced GMing techniques, optional

rules, to an in-depth coverage of adventure design, campaign management,

fantastic worlds, and even a simple mass combat / domain management system (it

is not ACKS, but it is mine). The guideline section is supplemented with

several monsters including extensive random encounter tables; treasures of all

sorts, and several random inspiration tables from adventure concepts to

fantastic civilisations, curses, islands and that sort of thing. The idea is

something offering practical help for novice GMs getting into old-school games,

and further advice and a smorgasbord of stuff for experienced people. The book’s

Hungarian version is written, illustrated and laid out, so there is a completed

manuscript there that “only” needs to be translated and slightly revised for

the international audience. Now that is 268 pages of “only”, which is an

obstacle. I cannot promise a fast-tracked release with my day job and other

projects, but as they say, “I’m on it”.

In the “wanted to do but didn’t”

category, we have Khosura: King of the Wastelands, the much-delayed city

and wilderness sandbox module. This is another case of “only”, where a lot of

the work has already been done, but the plans for Q1 2023 proved fabulously

optimistic. Perhaps a year later would be workable?

|

| Final Proofs With Small But Obvious Error |

The State of the Old School: Rebuilding

This year seems to be continuing

previous trends, which are not as exciting as grand upheavals and radically new

stuff, but sometimes, this sort of quiet rebuilding is for the better. It does

make for a shorter closing section, too, but them’s the breaks. For years, old-school

gaming was drifting apart and losing focus, slowly diminishing its value. That

process is probably complete. On one hand, this produces games which offer a

lighter form of old-school gaming, tempered with the aesthetics and design

concerns of games like 5e. The success of projects like Shadowdark and OSE

/ Dolmenwood demonstrates the demand for these middle-of-the-road solutions.

These are probably ideal for disgruntled 5e players who are looking for

something simpler and more free-flowing, but they will somehow have to find a

way to preserve the virtues of old-school play from the influx of dysfunctional

playing practices and the deluge of shovelware that success brings.

To an extent, you can also see some old

hands returning to the scene: a new edition of Swords & Wizardry has

been published (and don’t overlook the AELF License it comes with – this is the

quiet background work you would only notice if it was not there); Labyrinth

Lord and Dragonslayer seem to be focusing on B/X in their own way,

and there are rumblings around OSRIC as well, with a new edition targeted

as new players instead of publishers, and solid VTT support in Foundry. Adventurer,

Conqueror, King is getting a second edition, and Sword & Magic also

fits into the trend. It remains to be seen how much creative energy these

projects can muster. The specific challenge they will have to navigate (and

this is one I am acutely aware of) is that successful Kickstarters catering to

a base of collectors is not quite the same as relaunching living games

which produce healthy creative communities and good offshoots. Shiny new games

have a starting advantage here, while second editions, reprints, and expanded

editions have to play to slightly different strengths to succeed in the long

run.

|

| A Voyage to Thellas With Seven Voyages of Zylarthen |

As a third group, creative communities with

a renewed focus on the core of the old-school experience are also thriving, in

smaller size and a less commercial form. This is no longer the same as the OG

old-school community found on Dragonsfoot, Knights and Knaves, or the OD&D Discussion

forums – all of which have largely fallen quiet over the years – although it

shares some people and objectives with these places, and it resembles them in

their heyday. Their members were often people discovering old-school ideas as a

fresh thing, and they have moved from this rediscovery to self-improvement and continuous

refinement. Things like the No Artpunk Contest or the Classic

Adventure Gaming podcast (which now has a promising discord) are two examples of creative efforts

coming from these places, but there is more. These are not large endeavours,

but many of the guys involved have a high batting average, and this makes their

materials trustworthy – you can expect something good when you come across

their adventures, even if the production values are homemade and there are

occasional weird spots. Even some of the best adventures from In the Hall

of the Third Blue Wizard come from these quarters.

There are still places which are not explored

sufficiently well by this latter group. They have gotten great at dungeon

design, but much fewer have tackled wilderness scenarios, and only the mighty

Buddyscott Entertainment, Inc., has delved into cities (as far as I can tell).

Nobody has really made a properly old-school situation-based adventure that

does not suck. The NAP-II collection was overall very solid, but it was all

dungeons. In this sense, Fight On! and Knockspell magazines had

more to offer, and Dolmenwood promises yet more. I would love to see a

wilderness pointcrawl, a complex sandbox area, a strong open-ended city

adventure (in the vein of Istvan Boldog-Bernad’s Shadows of the City-God and

Well of Frogs – OK, I published them, but I published them because

Istvan is the absolute master of this sort of thing), or a setting gazetteer. The

NAP-III collection’s focus on high-level adventuring should deliver good

content in an underserved area (hopefully some extraplanar material as well),

but perhaps there should be room for a “Not a Dungeon” contest, too.

So that’s where it stands now, I think.

Work in progress, some of it looks like a pile of stones and timber, but it is

getting better where it matters.

Get to work, dogs!

|

| Motivation Will Be Provided |