How do you sell the idea of old-school gaming in a

country where few had heard of role-playing games before 1990, virtually nobody

before 1985, and where their popularity only took off in the decidedly not

old-school 1990s? The question has probably been pondered by everyone in

Hungary who has enjoyed and tried to spread this game style. A few old gamers

(and this means someone who had first met AD&D before 1993) can point at an

indistinct legacy of home campaigns, early game magazines and naïve fantasy.

More can recall to the Fighting Fantasy series, which had enjoyed incredible

popularity for a few years and spawned numerous professional, semi-professional and homemade imitations. Sometimes, it

is easy enough to bring up Howard and other sword & sorcery classics. But

for a certain gamer generation, my best bet has been to say, “It is a bit like the Chaos novels.” It

is a code word, and most of us know its meaning instinctively.

Let’s return to the early 1990s. One of the

important (sometimes beneficial, sometimes detrimental) features of this period

in fantasy fandom was the combination of exploding demand combined with very

inadequate supply. Before 1990, Hungary had been ruled by hard, speculative

science fiction with frustrated literary ambitions and few compromises towards

soft SF. Fantasy was right out. The Lord

of the Rings, a major popular hit, was released by a proper non-genre publisher, despite its

rejection by the literary establishment (including its translator, the future

president of Hungary between 1990 and 2000, who had once referred to it as “the

world’s largest garden gnome”). But suddenly, as things came apart, nothing was

off-limits. Genre fantasy and other pulps, then including science fantasy, UFO literature,

pornography, action novels, bodice rippers, New Age manuals, ancient astronauts

and who knows what else, started to appear as a trickle and then as a deluge,

mostly by grabbing the works of authors who were too distant or too dead to

protest about their royalties. Somewhere in that colourful, excited rubbish was

John Caldwell’s The Word of Chaos.

|

| A Classic |

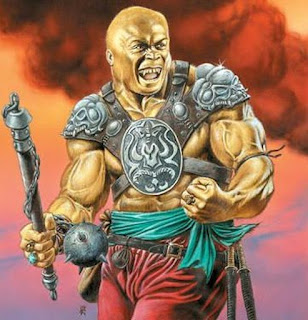

The Word of Chaos – with the phenomenally ugly cover of its first

edition – quickly became a hit, and was followed by the publication of

Caldwell’s other books. In a few years, it formed a pentalogy (The Heart of Chaos, The Year of Chaos, The Chaos of Chaos [you might get the idea someone was running out

of the titles] and Chaos Unleashed),

and established itself as one of the popular fantasy series in Hungary. It was

only a few years later that most of us learned that “John Caldwell” had never

existed, and was the pseudonym of Hungarian pulp fantasy fan Istvan Nemes all

along. Like his contemporaries, Nemes – who had worked as a programmer in

various odd jobs, and was long involved in SF fandom – chose the alias for

marketability. English genre authors, thought to be more authentic, commanded

more respect and sold much better, while Hungarians were just not taken

seriously. In time, Nemes also turned out to be several other people, including

Jeffrey Stone (whose Trilogy of the

Night is the best damn magic-meets-technology novel ever written, and the

work “Melan the Technocrat” comes from), David Gray, Mark Wilson, and even

more, including Julie Scott, Audrey D. Milland and Julia Gianelli (these were

for the bodice rippers). Conversely, to add to the naming confusion, Wayne

Chapman, the author of In the Month of

Death and Flames in the North,

the other major fantasy darling of

the early 1990s, turned out to be two people working under a common pen name –

and it was not much of a surprise when a third (in)famous fantasist

specialising in dark and visceral historical fantasy, “French-Canadian” Raoul

Renier, also turned out to be a domestic product in the person of Zsolt Kornya,

a protégé of Nemes of the

eighteen pseudonyms. But back to our main subject.

The magic of The

Word of Chaos (and the early Chaos books in general) is easy to understand.

It is adventure fantasy in the finest tradition, and to those in the know, it

was immediately obvious that it was closely based on AD&D – from its

distinctive character types to specific spells (which are memorised by the protagonists, a tell-tale sign if there ever was

one), it was all there, and it read like the transcription of a long-running

campaign. And what a campaign! This game featured classical adventuring

including daring raids on a pirate ship, the search for a powerful and lost

magic spell (the titular word of chaos,

something of a mixture between confusion and

power word: kill), dungeoneering,

plane-hopping and city intrigue. It never hesitated to kill off its characters,

even beloved ones, or yank the carpet from below their feet. In the best

picaresque tradition, it was full of ups and (a lot more) downs, playing out in

a dangerous and corrupt world full of uncertainties.

But what gave the stories their own charm was the

double-dealing and backstabbing that never happened properly in the dead boring Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms books.

The Word of Chaos featured an

ensemble cast of treacherous assholes who were bound together by nothing more

than chance and external circumstances, and proceeded to plot against each

other each time the GM seemed to have left them to their own devices.

Intriguingly, it was not the real evil characters who came across as total

scumbags, but mostly the good-aligned and neutral ones, who would just as

readily kill you as anyone else, but they would do it in the name of goodness

and decency. Druids, in particular, were portrayed as sanctimonious fanatics

who will never hesitate to murder someone “for the cosmic balance” or some

other sick prophetic ideology. When you meet these guys and girls, you’d better

have your weapons ready. (If there is anything specifically Hungarian about the

novels – and considering they were born of a fascination with western cultural

imports, there isn’t much that’s readily apparent – it is this utter disdain

for corrupted idealism, and a general sympathy for underdog characters caught

between massively powerful hostile forces.)

|

| Fighter/Cleric 3/2, AC 6, flail 1d6+3 |

Which brings us to the core feature of the series: the Chaos series is written from the point

of view of the bad guys. In the eternal war between Order and Chaos, Nemes

put his money on the side we are accustomed to see as antagonists. It is no

great hero or naïve farmboy who is used as the viewpoint character, but a

smelly, cynical, questionably aligned and not particularly heroic half-orc

fighter-cleric. Skandar Graun, the

hero of the series, walks into the novel as a low-level scoundrel, and while he

has an epic destiny of sorts (among

many others which, however, remain unfulfilled), he is little more than a crude

brigand with a low cunning and a hope of making it big. Skandar Graun is

likeable precisely because he is an asshole – although an underdog asshole. He

cheats, fights and betrays his way through the series, performs human sacrifice

for his patron, Yvorl, god of Chaos (Fiend Folio reference!), summons slaads (and

again...), misleads and steals from his companions, and he has a singular

important ability – he has a penchant for being the last man (well, half-orc)

standing when the excrement hits the fan.

When we meet him, we are introduced to Skandar

Graun through this passage:

“When he recalled his shameful deed, he angrily bit off a piece of the

wooden mug. What a dumb mistake he had made, he scolded himself. How could he

be so senseless to crush not just the traveller’s head with his club, but also

flatten his beautiful bronze-studded helmet! He hadn’t made a mistake like that

in years. Afterwards, he had tried in vain to repair the dented helm, but it

could not be helped. So did Skandar Graun inherit the stranger’s good steel

sword, his dangerous spiked flail, three throwing daggers and his bag of money;

along with a shield and a lordly set of armour – but his hairless brown head would

go uncovered. To make his misfortune even worse, the man’s cordovan boots

wouldn’t fit his enormous feet no matter how much he prayed and cursed –

although he had tried both. What more could he do? He stuck with his old,

battered and hole-riddled boots which had accompanied him since forever. Well,

at least he was used to them, and they didn’t stand out much from his usual attire:

his grease-stained, hairy leather pants hung dirty from his waist, and around

his knees, they were riddled with hazelnut-sized holes to provide ventilation.

And we should not think his glinting armour would stand out much from his

tattered clothes. To soften the baronial effect, Skandar Graun didn’t discard

his beloved old black cloak, which he had inherited ten years ago from his

foster father, and which had since assumed the effect of camouflage through

several tears and unidentifiable stains. The cloak also had an advantageous

feature by reeking of the smell of chicken guts, suppressing the disgusting

human odour emanating from the victim’s freshly acquired shirt.”

This was clearly heady stuff, neither Drizzt nor

Sturm and Caramon, who had always struck us as colossal bores and suckers

(especially in comparison). All of us wanted to be Skandar Graun or someone

like him in our games. Well, or at least Yamael, the mysterious, taciturn,

mint-chewing half-orc assassin, another one of John Caldwell’s characters... or

Marlena, the treacherous elven thief... or someone else from the long series of

treacherous lowlifes inhabiting the pages of his book. There were several of

them, as the series cheerfully went through characters like a shredder,

replacing them with newer and newer anti-heroes from a revolving cast.

But by the time we got the idea, playing Skandar

Graun or his demon-worshipping friends and enemies was no longer an easy option.

As it turned out, they had come from an earlier, more risqué and titillating

era of Advanced Dungeons&Dragons, full of demonic statues with gemstone

eyes, poison, deadly illusions, half-orcs, assassins, half-orc assassins, naked

chicks with bat wings, anti-paladins and devil-worshipping clerics. The

campaigns serving as a basis for The

Word of Chaos and its sequels took place around 1986 and 1987, while the

game in town around 1992 and 1993 was the bowdlerised 2nd edition

AD&D. This was the “Angry Mothers

From Heck” era, the TSR Code of Ethics era (see my

comments under this post), the patronising “let’s

protect the kids and their impressionable little minds” era. It was almost the

same game in body, but it was obvious to us it had been robbed of its spirit

and authenticity. The fuckers had stolen our half-orc assassins and

fighter-clerics, and given us worlds we immediately recognised and wrote off as

phony imitations; they tried to blind us with “official” AD&D novels which

never compared favourably to the earthy colours and dark wit of the Chaos

series.

We would play with what we had, but we sure envied

those older people who had access to the exciting stuff, real AD&D – and sometimes, in the fan translations that

circulated in the gaming scene in the form of worn photocopies, we could find a

hint or two of what had been; perhaps

an alternate class, perhaps a few pages of interesting magic items. Mind you,

this was pre-Internet: I would not see an authentic demon-idol 1st

edition PHB until 1997, and at the time, it was selling for the local

equivalent of a hundred dollars – tantalising, but out of reach. At the same

time, the Hungarian gaming scene itself was changing, and AD&D was mostly

supplanted by M.A.G.U.S., a locally written game (on which I may write later),

which, despite its many problems, offered some of the interesting adult themes

we were interested in.

|

| The Secret Ingredient |

Many years later, acquiring the genuinely

old-school modules and supplements, and getting to know the actual

personalities involved in the original Chaos campaign, revealed more pieces of

the puzzle. The GM behind the original games, it turned out, had been the same

“Raoul Renier” who had later made a name for himself as an author of dark

historical fantasy and a vocal RPG critic – at the time bitterly and vehemently

opposed to Gygaxian AD&D. But, even more intriguingly, I began to discover

that the seminal Word of Chaos was

actually based on two very identifiable modules, beginning with The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh

(although its role is only episodic in the book’s original edition), and

largely playing out in The Secret of

Bone Hill, featuring much of its sandbox environment from the town of

Restenford to the ruined keep and its dungeons. This was a revelation not just

because it put a concrete place behind our favourite teenage reading material,

but because it showed us how much more the

book (and presumably, the campaign it was based on) had given us beyond the

bare module. Bone Hill’s throwaway NPCs were spun into fully realised

characters: Locinda the half-orc, a minor mercenary NPC, appears as Bloody

Lucy, Skandar Graun’s long-term love interest; the wizard Pelltar becomes Peltar,

a servant of Order and the half-orc’s implacable nemesis; Restenford is a

bustling place of intrigue and danger, and as for the ruined castle and its

dungeons on Bone Hill, it is much more cool when it is used in the novel’s

showdown than it appears in writing (and it is not too shabby that way). Now

here was a proper way of using game materials – something nobody had shown us

properly in the 2nd edition era.

Of course, Skandar Graun’s adventures continued –

first in the initial pentalogy (these short novels total maybe 700 or 800 pages

altogether), and then through several more books. As they proceeded, the books’

connection to actual play grew weaker – the second novel, The Heart of Chaos features an extraplanar quest through the mad

plane of Limbo (structured as a multi-level “dungeon” reversing many AD&D

concepts – good mind flayers and evil silver dragons, and another treacherous

adventuring party), while the rest deal with the war between Order and Chaos. Our

favourite half-orc, who starts out as an unknowing pawn, eventually ends up

getting fed up with the crap he is given so much he ends up knocking over the

game board, more as a form of ultimate protest against all the misfortune and

death he had been surrounded by than in the hopes of actually accomplishing

something. Apparently, it was at the early stages of this campaign arc where

the original Skandar Graun had died, and the rest of his stories have less

connection to gaming – although they still make for good reading material. The

less said about the later sequels the better: – they felt like the series had

finally succumbed to burnout and a breakneck pace of writing, descending into

self-parody in an embarrassing way that still leaves a bitter aftertaste.

Ultimately, the series was also made into a fairly lacklustre and ponderous RPG

(that didn’t quite have the adventurous charm of the original series), and even

a badly botched CRPG (which, as it often happens in the externally funded

Hungarian computer game industry, was shut down by its publisher halfway

through its development and released as a buggy, half-finished mess).

Sounds like utterly brilliant trash. And that phenomenonally ugly cover also manages to be incredibly cool at the same time. How many illustrations can pull that off? ;-)

ReplyDeleteThat's what it is: honest, not terribly serious pulp fantasy with a lot of heart. And yeah, I have a special affection for that hideous cover - I have a tattered old copy signed by the author. :D

DeleteThe first two books are eternal favorites of mine. They are some of the best books I ever read. :)

ReplyDeleteTrilogy of the Night... oh, I loved it. I think I should read again the Chaos novels too.

ReplyDeleteI think the neutering effect of TSR's code of ethics, BADD, League of Angry Moms and suchlike is put way out of proportion. First, we haven't even heard of such things until many years passed, especially in distant post-communist Hungary, second, nothing on earth prevented anyone from playing backstabbing bastards even with the oh-so-bland 2nd edition sources if that was your heart's content (we certainly had our share of brutal blade-happy barbarians and Kali-worshipping child murderers - oh so cool, so evil or oh so juvenile). Third, there was the mass of 1st edition materials still floating around in massive amounts, so demons, devils, half-orc assassins or cocky cavaliers were hardly unknown to our tender young minds.

ReplyDeleteIt is easy to be cynical about things you could take for granted. Naturally, you always value the things you don't have higher than the things you do. If we had all that stuff at our fingertips, it would never have had the mystique of distance.

DeleteA lot depended on personal networks. People in the large city clubs (*cough* *cough*) probably had access to a lot more than people in private groups or outside the capital.

I briefly had contact with people who were involved in the club scene (this is also why I started with the domestic Combat and Magic instead of AD&D), but just as quickly lost this connection. They played with a lot of photocopied materials from several different sources (including the famous Ruby Codex, some 1st edition materials, and some stuff that was homebrewed), while we had the photocopied Psionic Handbook, and for some inexplicable reason, the anti-paladin NPC class, which one of the players JUST had to play. (He was killed by his own companions who were scared he would end up killing them.)

The risque stuff and 1st edition content was something we were vaguely aware of, and mostly missed, but couldn't get our hands on. For a while, we did not even have a monster book, and had to guess or make up our own.

Also, I have personal (and therefore probably overblown) experience with TSR's blandness creeping into our game and having a negative effect on our enjoyment. The more official materials we picked up, the less we ended up enjoying the game, until our group fell apart. Some of that was surely teenage stupidity, but I do believe TSR shares some of the blame as well. Especially in hindsight, the bulk of their generic AD&D material strikes me as pretty much useless garbage. The worlds are another matter, but we didn't play Ravenloft or Dark Sun.

That is, what I am writing about is not a thing but its absence.

Delete