|

| Cha'alt |

Cha’alt (2019)

by Venger Satanis

Published by Kort’thalis Publishing

Low to mid levels

* * *

Knee-Deep in the Zoth

Gonzo science

fantasy has a high pedigree in old-school gaming. Wild genre-mixing has been

with us since the campaigns of Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax, the publications of

Bob Bledsaw and David Hargrave, and has more recently produced such gems as Encounter

Critical (2004, predating the earliest retro-clones) and the great,

unfinished Anomalous Subsurface Environment. For something

affectionately referred to as “retro stupid” (Jeff Rients), this odd

platypus-like mutt of gaming history has produced some remarkably excellent

materials, and the expectations have thus been set rather high. So we come to Cha’alt.

The book has often been dismissed as a vulgar display of bad taste, the

product of some fringe weirdo with bad opinions, or juvenile fetish material

not worth playing attention to. It has a small but dedicated cult following who

swear it has merit. More often than one might think, these small cultish groups

are right, and everyone else is dead wrong. Sometimes, they are just deluded. And

thus, we are here.

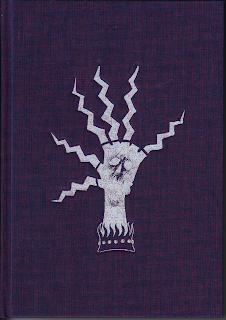

Cha’alt is a lavishly produced, colourful, 216-page hardcover printed on

heavy-duty, slick paper, with gold leaf embossing on the cover, and a psychedelic

dust jacket depicting something from a 1970s album cover. There is a generous

amount of colour illustrations and photos from Deviantart, most of them in

tremendously bad taste, from “photorealistic” fetish art to generic and

soulless colour pieces. As far as I am concerned, the art budget is wasted, but

production values do not really concern this blog, so we shall move on.

While layout is not

packed (white space and squiggly “magical glyphs” are abundant), there is a

surprising amount of material in the book. Where a significant portion of

old-school gaming has succumbed to the idea of minimalism, this is a rich,

extensive campaign book mostly focused on directly playable material. This is a

pleasant surprise: say what you will about the subject matter and the execution,

the book has its heart in the right place. It is not an exercise in creating

avant-garde literature, but giving you a rich grab-bag of stuff you can run out

of the book. More than that, it is actual, honest functional writing that

balances the setting’s peculiar flavour with the idea that information should

be accessible, easily understood, and of help to the tired GM. It does not go

into the weirdo formal experiments of presentation which have become

fashionable in recent years, but while the text will not win any writing

awards, it is competently edited, and does its job efficiently and

unobtrusively. There is even a functional, well-built appenix! In the realm of

ease of use, Cha’alt scores above much of the gaming field.

* * *

The Shores of

Cha’alt

|

| Retro stupid rides again |

Cha’alt’s setting is a blasted post-apocalyptic wasteland following a war

between the awakened Old Ones, and the planet’s highly advanced civilisation.

Various city-states and barbaric outposts inhabit the remaining land mass,

while interstellar opportunists have arrived to cart off the valuables,

especially the remaining pockets of zoth, the literal lifeblood of the defeated

Old Ones, and a main component of the super-valuable spice mela’anj. Of the

great dungeon-complexes that have risen over Cha’alt, none are as formidable as

the fabled Black Pyramid, a massive structure that has risen anew from beneath

the sands. This is a high-energy setting with a crazy and enthusiastic

anything-goes approach, from sandworms to space sluts, and from shameless

Cthulhu flogging to monster cults. Gonzo games live or die by the way they cobble

together their seemingly incompatible influences; the internal tension is part

of the appeal, and being a little crazy never hurts.

The supplement’s

first section is taken up by setting background and setting-specific miscellany

– a grab-bag of stuff for your Cha’alt campaigns. If you want a random, goofy

mutation chart, you will find it in the desert survival rules, while the

description of the Domed City has a cyberware table to juice up your

characters. This is a fun integration of rules and setting, and the section

where the supplement is at its closest to the fabled Wilderlands of High

Fantasy – a high point of creative, haphazard, play-friendly content.

Factions with their typical representatives, and desert critters are described,

although there are no random encounter charts (which would be one of the most

important things to have in a sandbox setting), and the monster roster is

rather limited with only seven new critters (there are several more scattered

over the subsequent chapters). The same is the case for some of the

supplemental material or random charts and rules, which are found hidden later

in the book – a table of simple psionic abilities, an NPC motivation chart,

random ability score arrays... bits and pieces that come up during play.

|

| Here kitty kitty |

The core of Cha’alt

is centred around four adventure sites: two smaller dungeons (Beneath

Kra’adumek, 17 keyed areas; Inside the Frozen Violet Demon Worm, 23

keyed areas), a “home base” style location (Gamma Incel Cantina, 69

keyed NPCs), and a large, three-level “tentpole” dungeon (The Black Pyramid,

111 keyed locations). Unfortunately, it is the short intro scenario, Beneath

Kra’adumek, that is the really good stuff, and the rest have a growing

number of problems. But Beneath Kra’adumek is good, partly because it is

designed as a real dungeon. There is a decent, meaningful layout combining

caverns and passages; there are guarded sections to avoid or eliminate,

prisoners to free, mysterious stuff to mess with, weird monsters (the

centrepiece being the demon cat-snake) and duplicitous NPCs to kill, fool or

befriend; and it has a sequence of simple, memorable setpiece encounters. Ways

to poke at other dimensions and screw things up (including making 1/6 of

Cha’alt’s population disappear forever). Fanatical demon-worm cultists absorbed

in their evil activities. Cryogenic pods to awaken ancient pre-catastrophe

sleepers. Individualised treasure. It is a dynamic scenario that could go a lot

of ways due to the variety of NPC/monster/device interactions, and even feels

like a goofy sort of Star Wars locale – great for an action-packed intrusion

into the fortress-dungeon of an evil space cult, three “princesses” (well,

big-boobed space sluts) included. This is top-notch, and unfortunately, as good

as it gets.

Inside the

Frozen Violet Demon Worm is a great concept –

exploring the intestines of, well, you get the idea – but Cha’alt’s deeper

flaws start to emerge. First is the degeneration of the maps. An arbitrary

dungeon (Beneath Kra’adumek) offers good exploration potential, while

the demon-worm’s interior is an enormous fleshy tunnel with a bunch off

side-chambers in its folds. You approach the locations, you do the encounter. This

is the Monty Haul dungeon in its original sense – a series of “doors”

along a corridor to open for random stuff ranging from a young woman chained to

a stone column crying out for help (concealed Ktha’alu spawn with some really

god magical loot), a group of insectoids battling a flesh-sac detached from the

slowly thawing worm, or an enormous stone head worshipped by savage

brutalitarians (lazy Zardoz reference), a lost pirate ship, or a bunch of

skeevy guys playing high-stakes poker around a scrap metal table. Why? Rule of

cool, that’s why.

|

Retro, retro

stupid, retro utterly

freaking dumb |

This is

super-arbitrary, and unlike the cultist lair, has no good sense of place. Why

don’t these encounters wander off a little? Why don’t they interact if they are

right next to each other? What happens if the party runs deep into the worm,

triggering them one by one (and how could the GM handle the logistical chaos of

juggling 8-12 setpiece encounters)? It is a mess, with little to connect the

random bits and pieces. It feels like a “ghost train” type deal from an

amusement park, with dioramas of animatronic monsters leering at you from the

sides. The structure is horrible, and whatever dynamism is present in the

encounters is probably going to be wasted. They are still rather good on the

individual level – the author’s skill for punchy, self-contained situations and

setpieces lifts up the material. If these were spaced less tightly, and placed

within a more interesting, better designed dungeon environment, this would be

another good one.

Gamma Incel

Cantina is the Mos Eisley cantina from Tatooine,

but on Cha’alt. If you have an interest in gambling, whoring, illicit deals,

information or odd jobs, this is a good place to visit if you know how to get

in (it is behind a cloaking field). The presentation is questionable, but the

content is good enough. Basically, you get a map, a brief description of the

cantina’s main areas (from loos to gambling tables to its VIP lounge), then 69

(tee hee) NPCs keyed on the map in colour-coded groups to make things a little

more accessible. This is, obviously, completely useless for anything other than

hitting up 1d6 randos and interacting with them, and treating everyone else as

a homogenous crowd. On the other hand, the paragraph-long NPC descriptions

offer brief, fun profiles so hitting up those 1d6 randos is going to get you

something. The list, appropriately enough for the author’s interests, starts

with P’nis Queeg (“Pilot; just parked his starship; yellow skinned

banana / penis headed alien with swollen ganglia. He’s holding a brand new

plumbus.”), and includes people like Treena (“THOT, human; blonde

hair, blue eyed space Muslim; smoking long, thin hookah; likes humiliation and

spanking”), Halvern (“Sentient chartreuse vapor inside

environmental suit; fake mustache painted on helmet visor; uncontrollable

giggling – that’s why they call him “laughing gas.””) or Bolo (“Droid;

bounty hunter; camouflage and rust-colored; spritzing WD-40 on plate of myna’ak

wings; head of engineering on nearby space station.”) You get the idea. The

sleazy truck stop/titty bar vibe is spot on, and it works decently as Cha’alt’s

Keep to Cha’alt’s Borderlands.

|

| The Very Naughty Tetrahedron |

We now come to

the main attraction: The Black Pyramid rises from the wastelands, descending

into an underworld most mythical, or at least moderately horny. This is

obviously the campaign lynchpin not just from the size, but all the side materials.

We get a rumours chart, and random encounters complete with specific monsters (from

the dreaded night clowns to hunter-killer droids, fruit folk, pizza delivery

and bat-winged eyeballs) and unique NPC groups (lost Romans, alien looters, suspicious

hooded guys of all sorts). A “what happened while you were away” chart! A

“leaving the pyramid” chart (travel 1d30 years into the past/future and wipe

most of the campaign – woo-hoo)! Six new gods! A “you dumbass slept in the

pyramid” chart! And so on. So far so good.

|

"Have we reached rock bottom yet, guys?"

"Not yet! Everybody, dance!"

"My anus is bleeding!" |

But then... yes,

the problems of the book come back in force, and are multiplied fourfold. The maps

are chaotic gibberish. Any semblance of structure or order (or even inspired

chaos) goes out the window, and what we get is a bunch of randomly shaped and

sized rooms connected by short, randomly patterned corridors (these seem to

have no distinct function, or the reference just fails me) between random

clusters of colour-coded rooms accessible with special crystal keys. This

childish mess does not look like a pyramid – even a severely corrupted one – lacks

meaningful height differences or even connecting stairs (what you think are

three dungeon levels are actually a single flat plain), has no spatial order to

accommodate orienteering or exploration, does not feature actual dungeon

navigation challenges (even less so than the frozen demon-worm), and it is

overall very repetitive in its formal structures. The room descriptions have no

relation whatsoever to the room shapes and sizes. To make it short, the map is really,

really terrible, lacking any redeeming qualities.

There is

something about the encounters that was grating. Maybe my patience was wearing

thin, or maybe it is truly repetitive, but one of the reasons this review is

overdue by several months is that I just could not press on with it. It is just

one pop culture reference setpiece after the other pop culture reference setpiece.

Now... this can work if there is some other kind of connecting material

to add variety (say, an interesting dungeon map to navigate, or challenging

combat/exploration situations and a few clever traps), but it is missing them

altogether. The lazy content also shows its limits. Sometimes, recognition

still elicits the Sensible Chuckle, but that well soon runs dry, and you start

to scrutinise these encounters with a more critical eye. And many of them do

not cut it – they are often static, convoluted for the sake of telling a lame

joke, or don’t offer much interesting interaction. And those lame jokes, they

are getting lamer and more one-note. Here is a room housing anthropomorphic

fruit (#13). Here is a stereotypical podcast guy doing an interview (#14).

Here is the Carousel room from Logan’s Run (#15) – all right,

this is OK. Here is a room with a clone of Rob Schneider trying to convince a

young woman to pay him for sex (#16). Here is a room with a statue of

Gonzo, of Sesame Street fame (#17). “Inspecting Gonzo's nose reveals

a tiny catch underneath, at the base. Manipulating it opens a compartment

located in his crotch. Inside is a battered trumpet. Playing Gonzo's trumpet

summons a Buddhist monk (appearing in 1d4 rounds) who walks into the room and

sets himself on fire, providing enough light and warmth for several minutes

before it goes out and what's left of the monk is carried away like sand in the

wind.” There was an opportunity with the Black Pyramid to present some kind

of otherworldly, metal-inspired, high-energy dungeon. If you’ve got a black

pyramid in your game, you kinda owe something to your readers. Well, Cha’alt’s

Black Pyramid is not otherworldly; it sells out all its potential at one

tired joke a pop. It is all so tiresome.

|

| Here is another one for free |

Zothferno

|

| Your dungeon is offensive! |

As the post may

suggest, Cha’alt is not an easy thing to review. It is a giant

collection of the good and the bad, mixed in with the happy medium of

“questionable”, and it is not easy to separate the wheat from the chaff. At its

best, it is high-energy gaming with a lot of personality, and a very specific

flavour (space/Cthulhu sleaze). It would be a mistake to write it off on the

basis of this content – like it or not, this is what it intends to do, and what

it intends to be. Those who call it skeevy or sexist are only doing the author

a favour, since this is what he wanted to do. To cite the late, great József

Torgyán, head of Hungary’s Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic

Party, “A lawyer with litigation, and a fine lady with a hard instrument,

cannot be threatened.” But does Cha’alt succeed on its own terms?

As far as I am

concerned, one of the supplement’s main draws is something that some may identify

as a flaw – it is not a thoroughly polished product, but something that shows

its origins as a bundle of the author’s home campaign notes. It preserves the

enthusiasm, and does not reduce the material to a dry treatise. It invites

questions and engagement. There is a definite sense of a dog-eared folder of faded

printouts, scratch paper, and session notes behind the book. It is charming,

and ironically, more conductive to actual use than many books that look more

smooth, but are not presented with table use in mind. It is as accessible as a

slightly cleaned up collection of GM notes, and a fun glimpse into a madman’s

mind.

There is also

something to be said about the modules’ ambitions. They are deeply flawed in

multiple ways (as detailed above), but they are not gated by level and do not

pull punches. You can easily meet enemies who are way more powerful than you

are. You can also beat them up and take their high-tier loot or obtain powers

beyond your meagre abilities. You can find yourself bargaining with major

demons, inadvertently unleashing planetary devastation, or pull off major

campaign-altering victories. Some of this is lolrandom stuff that depends too

much on die rolls or (un)lucky encounters instead of player skill or meaningful

choices that lead to logical consequences, but it is there nevertheless, and it

can be glorious even in this flawed form. It is writ on a large scale, and

allows the players to win big or lose big.

Third, it shows

variety and imagination on the encounter level. Things on Cha’alt are

unpredictable (to say the least), but they are always colourful, and feature

fun interactivity – NPCs and plotlines sketched up willy-nilly with a few broad

strokes, there are knobs to mess with (some of them blow up half the world, but

that’s OK), and a lot of the material is hand-crafted, specific – although the

magical treasure is also too plentiful; you can barely take a few steps without

finding a javelin +1 or a freeze-ray. Many of the pop cultural references are

lazy, but at least many of them make for a compelling set-piece.

Here is the

problem, though. Cha’alt is cursed by a curious sort of laziness that’s

apparent even if you consider this is a 200+ page hardback crammed with gameable

content. It falls apart on the levels above the encounters, and has little

discernible structure to it. Things are sometimes connected a little (albeit

haphazardly), but mostly, it is just throwing things at a canvas to see if it

sticks. Is there a pattern behind the random ideas, or is it just you? It is

probably just you. The trick works in the comparatively small and tightly

designed starter dungeon, but it increasingly becomes apparent Mr. Satanic is

bluffing. The lack of structure and the utter scattershot randomness of the

material makes it hard to apply player skill to the modules, to treat them as challenging,

complex problems or even real places. This is where the diorama/animatronic

monster issue comes back to take its revenge. The environment cannot be known

and mastered because there is no environment, only an illusion of one.

The amount of interaction obscures this problem, but never fully resolves it.

|

Your Dungeon is a Cancerous

Growth of Intertextuality and

Postmodernism. REPENT! |

And it also suffers

due to the sheer excess of pop culture citations. Any conceivable part of

cult/geek media is digested and reconstructed in Cha’alt to form the

majority of its encounters. While surely one of the greatest collections of

genre and pop culture references, Cha’alt does little to integrate its

disparate influences into a greater whole, or at least give them its own spin.

The approach it takes is disappointingly literal, and often falls flat. When Anomalous

Subsurface Environment draws from He-Man, it adapts the material to its

setting, the Land of a Thousand Towers, and the result is always a great fit

which transforms the spoofed material just enough to stay recognisable, yet add

a new angle or a clever gameplay twist. Say, “Monsator, Lord of the Stalks” is

obviously an homage to Evil Megacorporation Monsanto, but he is also a fully

developed, compelling villain of a wizard who is interesting beyond the quirky

reference. Monsator is also one idea among many, most of them original.

When Cha’alt does

something similar, it mostly just plops down its direct references randomly,

and tries to skirt by on the strength of star recognition. Sure, Mr. Satanic

betrays an encyclopaedic knowledge of late 20th century cult stuff

and esoterica, but a Videodrome reference next to a Logan’s Run reference next

to a tiki bar next to a movie theatre showing Escape From New York does not

start living together without some effort to make a coherent whole out of them.

The city of “A’agrybah” is plainly Agrabah from Disney’s Aladdin, “just on

Cha’alt” with some surface details like a spaceport and a human sacrifice

tradition. Sure, there is supposed to be chaos and wild leaps of imagination,

but that is just part of the work. Here, the other part is very often missing,

and it is all just a post-modern mish-mash of citations upon citations. Is this

because the author knows no better? Far from the truth! When he makes an effort

to tie things together, as with the setting background, he succeeds fairly

well. It just doesn’t happen often enough, or I guess well enough to bring out

the sort of transformative quality which makes for a truly great gonzo

setting.

Ultimately, these

two central flaws are what makes Cha’alt only “good enough” and not

actually “good” or “great” – they are omnipresent through the book, and cannot

be easily fixed. There is something really good in the setting, and with better

structure, the basic concept could excel. Where Cha’alt is good – the

starter dungeon, many of the individual encounters, the no-nonsense

campaign-friendly presentation – it is deservedly good. As it is, though, it is

a deeply flawed book, although never without charm, or generously endowed space

doxies, bless ‘em.

No playtesters

are credited in this publication. It has apparently been very thoroughly tested,

although often in a fairly peculiar manner, as text chat-based random pickup

games over several of Mr. Satanis’ lunch breaks.

Rating: *** /

*****